For years, college presidents and other higher education policy wonks have promoted the lifetime earnings gap between high school and college graduates. The figures cited have ranged from $1.1 million to $1.9 million over a working person’s career. But sometimes, recent graduates accept work below the expected salary range for their degrees, which means underemployed college graduates experience this earnings gap differently.

The Global Auction

In 2011, I reviewed a newly published book, The Global Auction. The three British economists who co-authored the book wrote that the American Dream once emphasized higher education as the path for the lower and middle classes to move up—but the dream is in trouble.

The book highlights concerns about the American Dream and the authors chose to emphasize higher education’s role in social mobility.

Authors Phillip Brown, Hugh Lauder, and David Ashton wrote that Americans with college degrees were sheltered from price competition if educated talent was in limited supply or only available from equally expensive countries like the UK, Germany, and Japan.

A global price competition for expertise was created by:

- A quality and cost revolution in emerging economies that produced high skill, low wage workers

- A doubling of the supply of college educated workers in affluent and emerging countries over the past 10 years (2000-2010)

- The adoption of new technologies by companies that increased the potential for standardizing a higher percentage of technical, managerial, and professional jobs

- The business community’s trend of hiring the best and brightest students regardless of location in the world

The authors point out that an opportunity trap is created when everyone works toward the same strategy. This could include earning a bachelor’s degree or working longer hours to impress the boss. Among their recommendations for changing this scenario was to increase the number of graduates with STEM degrees and focus on hiring workers based in the U.S.

While I happened to think that The Global Auction was an excellently researched and informative book, there was little press about the authors’ warnings at the time.

What’s the Real Wage Advantage of a College Degree?

Nearly a dozen years after I reviewed The Global Auction, I wrote about the high school to college earnings gap. I cited a chapter from The Global Auction titled High Skills, Low Wages.

The authors wrote “there is a problem using averages to represent the fates of those with a college education. The averages go up when a very high earner’s wages are included but the median does not.” They recommended using “an income parade” of earnings from the 10th percentile through the 90th and noted that “only males and females in the highest category (90th percentile) of bachelor’s degree earners enjoyed any significant growth in real income since 1973.”

In the same post, I cited a 2021 research paper, The College Payoff: More Education Doesn’t Always Mean More Earnings, authored by Anthony B. Carnevale, Ban Cheah, and Emma Wenzinger of Georgetown University. Their paper provided several notable statistics as well as a few charts copied below.

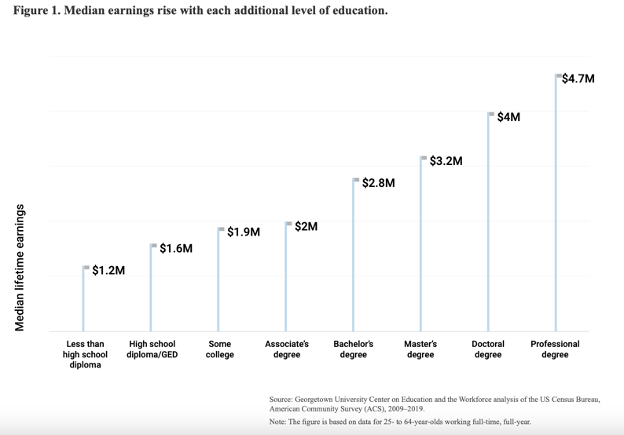

Their first data statement was that median earnings generally increase with more education. Figure 1 shows that progression.

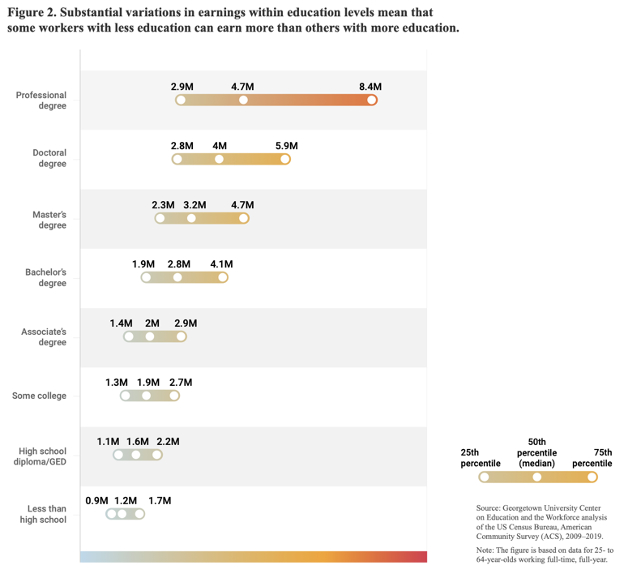

However, the researchers noted that there is substantial variation in earnings within degree levels. As a result, there is overlap between the high earners at a lower education attainment and the lower earners from a higher education attainment. An example is bachelor’s degree workers at the 25th percentile earn the same as the median of workers with some college. See Figure 2 below.

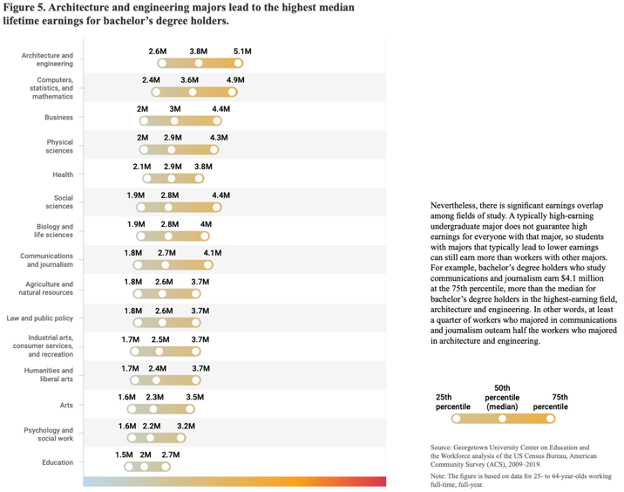

The researchers also published a chart (Figure 5 below) that displayed the differences in lifetime earnings for various bachelor’s degree recipients. Note that the top five are STEM and business programs. Also note the wide variation between the 25th and 75th percentiles in each program as well as the substantial overlap between programs and earnings.

In my original discussion of The College Payoff, I wrote that the most salient recommendation of the researchers was that career counseling for students should expand and improve.

Talent Disrupted: College Graduates Underemployed

Last week, the Burning Glass Institute and Strada Institute for the Future of Work released a paper titled Talent Disrupted: College Graduates, Underemployment, and the Way Forward. Individuals credited for substantial contributions to the report include Andrew Hanson, Carlo Salerno, Matt Sigelman, Mels de Zeeuw, and Stephen Moret.

The premise of the report continues along the lines of other publications, including the two cited previously. “College is not a guarantee of labor market success” could be useful as the report’s overview.

The executive summary of the report continues with this statement:

“(Among) workers who have earned a bachelor’s degree, only about half secure employment in a college-level job within a year of graduation, and the other half are underemployed…some graduates who are initially underemployed eventually secure a college-level job, but the majority remain underemployed 10 years after graduation.”

The researchers used a combination of online career histories of tens of millions of college graduates, as well as census microdata for millions of graduates. It’s important to note that their focus was on workers with a terminal bachelor’s degree, even though many four-year college graduates earn an advanced degree.

Employment Outcomes for Recent College Graduates

Finding the right first job after college graduation is critical for most workers. Graduates who start out in a college-level job usually remain in a college-level job. Graduates in a college-level job usually earn 50% more than those who are underemployed.

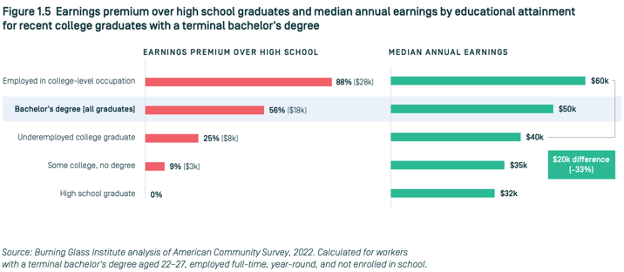

On the other hand, graduates who start out underemployed usually remain underemployed 10 years out (terminal degree bachelor’s graduates only). Most (88%) underemployed college graduates are severely underemployed – working in jobs that only require a high school degree or less. Figure 1.5 illustrates the financial impact of underemployment.

Factors Influencing Underemployment

The following are included among the factors associated with unemployment, meaning whether a graduate will land a college-level job:

- Demographic characteristics

- Graduate’s college major or degree

- Internship participation during college

- Institutional selectivity

- Institution type

- Institutions’ share of low-income students

- Where graduates live and work

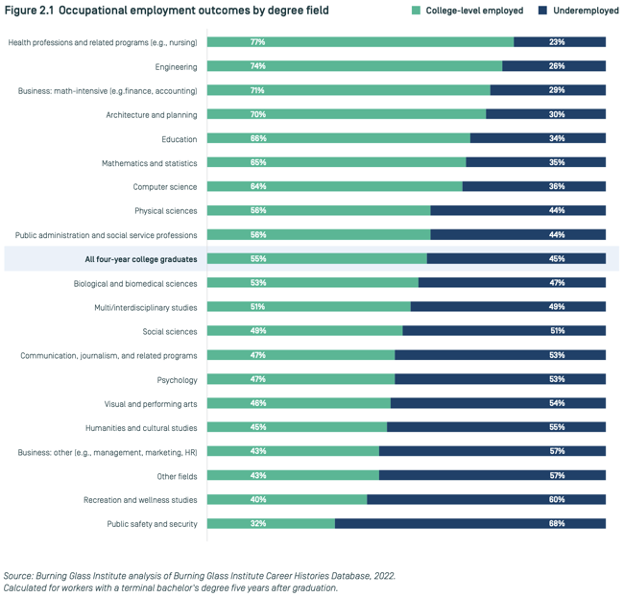

The researchers write that a graduate’s choice of degree field is strongly related to their likelihood of obtaining college-level employment. They claim that the degree field matters more than the college the graduate attends. Graduates with degrees in fields with quantitative rigor have greater odds of securing college-level jobs.

Figure 2.1 illustrates the employment level outcomes by degree field for the more popular degree programs.

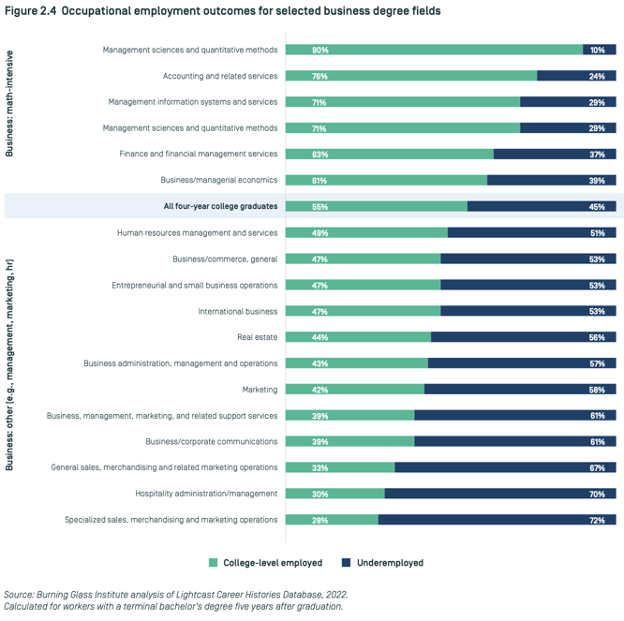

Figure 2.4 illustrates the difference between business-related degrees that are math-intensive versus those that are not.

The researchers reported that health, education, and engineering majors at inclusive public colleges and universities have lower underemployment rates than biology, psychology, and communications majors at selective public colleges. I am not surprised. In the past, some of those institutions may have been standalone teachers’ colleges and nursing schools.

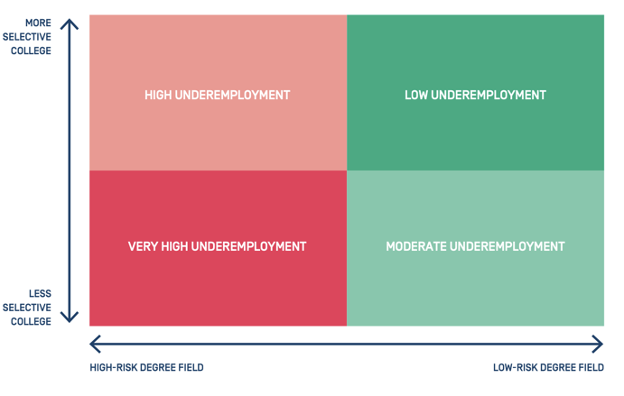

A decision matrix that grids the relative risk of a degree field with the selectivity of the college illustrates for people in similar degree programs. It tells us individuals who attend a selective institution are likely to have better employment outcomes than those attending non-selective institutions. This is not the case when the selective institution graduate from a high-risk program is compared to the less-selective graduate from a low-risk program.

Escaping Underemployment

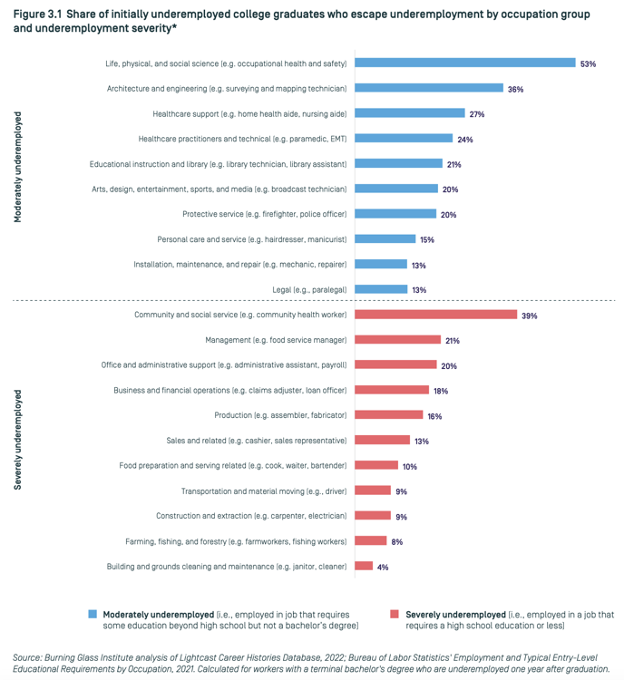

The researchers note that a “meaningful share of underemployed graduates is eventually able to escape into college-level employment.” Mapping the pathways for escape provides an understanding of what may help others in the future.

Graduates who enter an occupation group with a moderate underemployment percentage are more likely to attain college-level employment than those entering a severe unemployment group. Figure 3.1 illustrates these groupings and the percentage of graduates who “escape.”

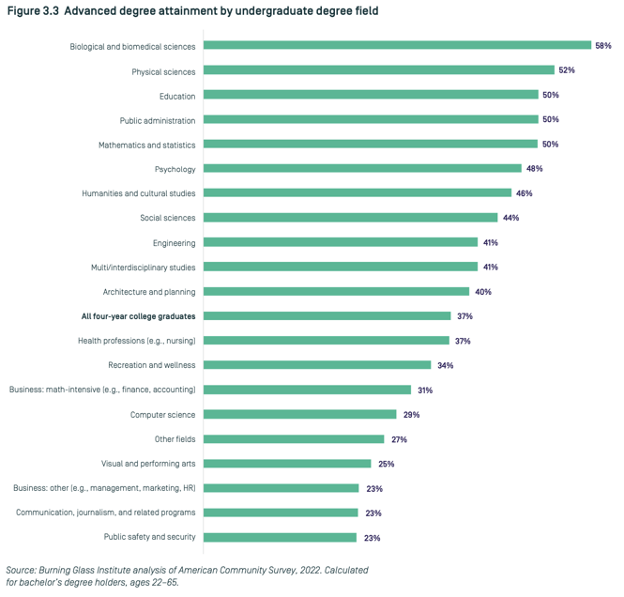

In the report’s introduction, the researchers wrote that their report focuses on terminal bachelor’s degree holders. At the same time, advanced degrees can be a pathway to escape underemployment. They noted that 38% of four-year college graduates go on to earn an advanced degree. See Figure 3.3 for the advanced degree percentages by field.

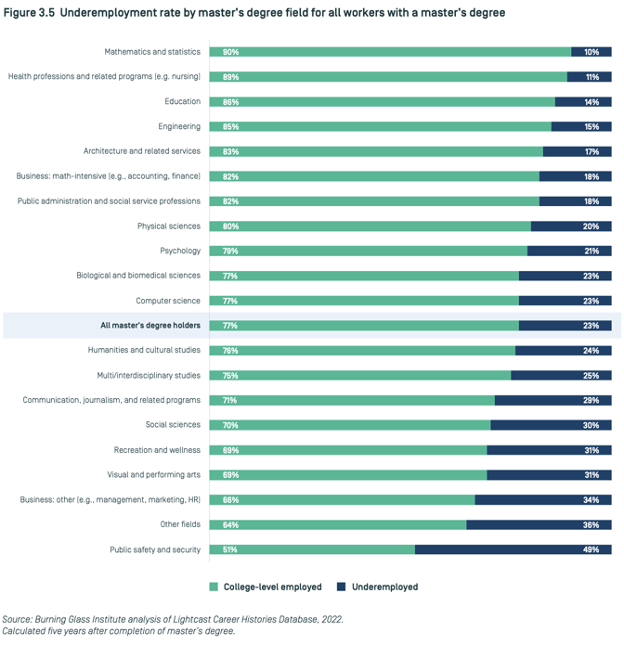

Master’s degrees are the most common advanced degree, held by 75% of the bachelor’s degree grads who complete an advanced degree. Not all those master’s degrees yield an escape from underemployment. Figure 3.5 illustrates the relative underemployment by degree field.

The researchers recommend four strategies for escaping underemployment. These are:

- Complete an advanced degree program.

- Secure a starting job with better odds of escape.

- Consider opportunities in vibrant regions with abundant college-level jobs.

- Attain more quantitative skills.

The final summary of the report provides these four recommendations:

1. Expand Paid Internship Opportunities

Ensure that college students have access to at least one paid internship. Only 29% of college graduates complete a paid internship. Policymakers should incentivize employers to expand paid internships for college students.

2. Enhance Employment Data Transparency

Ensure everyone has access to clear employment outcomes by college and degree program, with earnings and occupation data included. The researchers recommend that the Department of Education (DOE) consider adding occupational outcomes information on the College Scorecard.

I recommend the Department of Education include data from all graduates, not just those who borrow. Institutions successful at enrolling working adult students from specific industries or employers that reimburse tuition should be rewarded with their earnings and no debt data instead of penalized by their absence.

3. Revamp College Career Coaching

Provide quality education-to-employment coaching to every college student. The ratio of students to career services staff at colleges is 1:2,283. In four decades, I’ve never heard a single bachelor’s degree recipient compliment their college’s career services department. That ratio confirms why.

4. Expand Access to Lucrative Degrees

Ensure that every student can access degree programs that lead to well-compensated, college-level employment. The researchers note a strong correlation between programs with high delivery costs and those with strong restrictions to access.

This suggests that state funding formulas disincentivize institutions from expanding enrollment in high-cost programs, even when employer and student demand is high. Nursing programs at public institutions are a perfect example of this situation.

Final Observations About Underemployed College Graduates

I am a fan of the database collected, maintained, and analyzed by Lightcast, the company formed by a merger of Burning Glass and Emsi. The Burning Glass Institute and Strada Institute for the Future of Work have published an excellent report, one that I hope enhances outcomes for college students.

This is not the first report (and won’t be the last) that highlights the importance of a graduate’s degree program as well as other items like demographics, selectivity of the institution attended, paid internships, geography of employment, etc.

The section about post-graduate degree attainment was helpful. While the researchers reported the percentage of bachelor’s graduates who earn a graduate degree (38%), it would be interesting to know the percentage of graduates of selective institutions that earn a graduate degree. I suspect the percentage is much higher than the average reported.

I wrote earlier that an apt summary of the Burning Glass/Strada report could be “college is not a guarantee of labor market success.” On average, that quote is correct. At the same time, the outcomes for those able to receive adequate counseling, those able to attend selective institutions, and those able to gain access to resource constrained STEM programs at public institutions are clearly better than the outcomes for those who can’t.

The final recommendations of Talent Disrupted were titled Recommendations for Policymakers, Colleges and Universities, and Students (pg.42). Positive outcomes for our college graduates should be a desired outcome for all three of these groups. Each of them would be well-advised to read this report.