For nearly two decades, I led the online American Public University System through the early, medium, and high enrollment growth stages of online courses and degree programs. In those early years, I knew and worked with many of the major contributors to the development and improvement of online education and understood online course pricing very well.

Our team at APUS shared course improvement suggestions and outcomes data by publishing papers and speaking at conferences such as the Online Learning Consortium (OLC), formerly the Sloan-C Consortium. During those years, APUS was recognized with at least five OLC Effective Practice Awards and the Gomory Award, which recognizes the top institution dedicated to online learning quality.

I’m proud of the work that the faculty and staff at our institution and many others did to increase the positive perception of online courses and programs with students almost everywhere. The quick pivot of traditional campuses to online during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic was due to many of these advances by pioneers in the field.

Ecoura Eduventures’ Chief Research Editor, Richard Garrett, recently predicted that in 2025, the number of students enrolled in online courses will exceed the number of students enrolled in college who are taking no online courses. His prediction triggered a smile from me. However, there continue to be skeptics of online education.

EdTech+’s Glenda Morgan’s weekly blog last Friday alerted me to a recently published Hechinger Report article that asks why online courses cost the same as traditional courses. Ms. Morgan questions some of reporter Jon Marcus’s sources and claims about online education and muses why no one with substantial online experience was interviewed for his article. After I read it, I thought I would provide some thoughts and commentary.

All Online Programs Do Not Cost the Same

Mr. Marcus leads off his article with a story about a student living in Austin, Texas who was interested in pursuing a master’s degree in public health. The traditional, face-to-face program was more money than she wanted to spend, so she conducted a search of online programs. She was “surprised” that the costs were the same as in-person programs.

To consider the many reasons why online courses and programs may cost the same at most institutions, I believe you must take a step back and consider the reason(s) why the online courses and program(s) were developed.

If online courses and program(s) are developed to supplement the traditional mode of education for existing traditional students, offering them at the same price makes sense even though the student is taking the online class from their dorm room or some other location during the semester. All other campus-based services are available to those students, with only the instructional mode (online) changing for their convenience or some other purpose.

If the online courses and program(s) are developed to expand student enrollments, at a minimum, the availability of academic advisors and other student support services will likely need to expand to meet the needs of the non-campus-based students. Marketing costs will increase since campus-based and online students usually do not meet the same profile.

Unless the courses are synchronous versions of a live in-person class, additional costs will be needed for the instructor(s) teaching the separate online courses. In addition, marketing and advertising expenditures will need to increase to market the online only courses and program(s).

Online courses and programs offered by the top 25 colleges and universities in terms of online enrollment are scalable. They are also priced independently. If I were the prospective student, I would have searched that group for the lowest-priced and specialty-accredited online MPH degree. I’m sure the costs vary by institution.

A 2022 paper published by Ruffalo Noel Levitz indicated that the average marketing expenditure for online programs at public and private non-profit universities exceeded $1 million per year. For some, those marketing expenditures are even greater (one institution reported more than $8 million in marketing – the largest institutions likely spend approximately 20-30% of annual tuition revenues on marketing). Organizations like Kantar, Vivvix, and Nielsen provide data about marketing spends in online education for their subscribers. Unfortunately, I don’t have access to that data.

In the early years of online learning, colleges and universities were either in the “build it internally” camp or signed an agreement with an online program management (OPM) company to take over the development and marketing of the online courses and program(s).

During the initial development and implementation of a new online program, it is unlikely that a seat in an online course can be offered at a lower price than the existing charges at an institution. As Mr. Marcus writes, “83% of online programs in higher education cost students as much or more than the in-person versions.” I’m not surprised.

Implementing technology at a university is not cheap, particularly when it does not benefit most of your students. To recover the costs of the technology, you must reach a steady state enrollment where the contribution margin of the incremental online students covers the amortization of the technology costs incurred.

Sadly, Mr. Marcus chooses to include comments from left leaning think tanks without including any commentary from people working for the universities that decide what the cost of online courses and program(s) will be. Achieving the “economies of scale” that he cites as the potential to reduce the cost of online courses takes time and marketing dollars to fill the empty seats in new courses and programs.

Marketing Online Degrees

I published a blog article in January 2023 and posed the question whether incremental online enrollments of working adult students would bail out higher ed. I provided a logical explanation backed by an academic research paper that only five percent of the 40 million adults with some college would return to complete a college degree.

I reviewed data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) that indicated 58% of two million bachelor’s degrees awarded between 2019 and 20 were concentrated in six fields of study: business, health professions and related, social sciences and history, engineering, biological and biomedical sciences, and psychology.

I analyzed the online advertising and marketing for the top eight concentrations in business administration. I created a table depicting the Google search results for the top 10 colleges or universities in each of the eight concentrations and noted whether the result was paid search or organic (unpaid).

It was not surprising to me that only 44 colleges and universities were listed in the 80 outcomes (8 concentrations times top 10 in each). Eight universities were listed in 35 of the 80 search results – Southern New Hampshire University (7), Western Governors University (7), Purdue University Global (4), University of Louisville (4), University of Phoenix (4), Arizona State University Online (3), Regent University (3), and Strayer University (3).

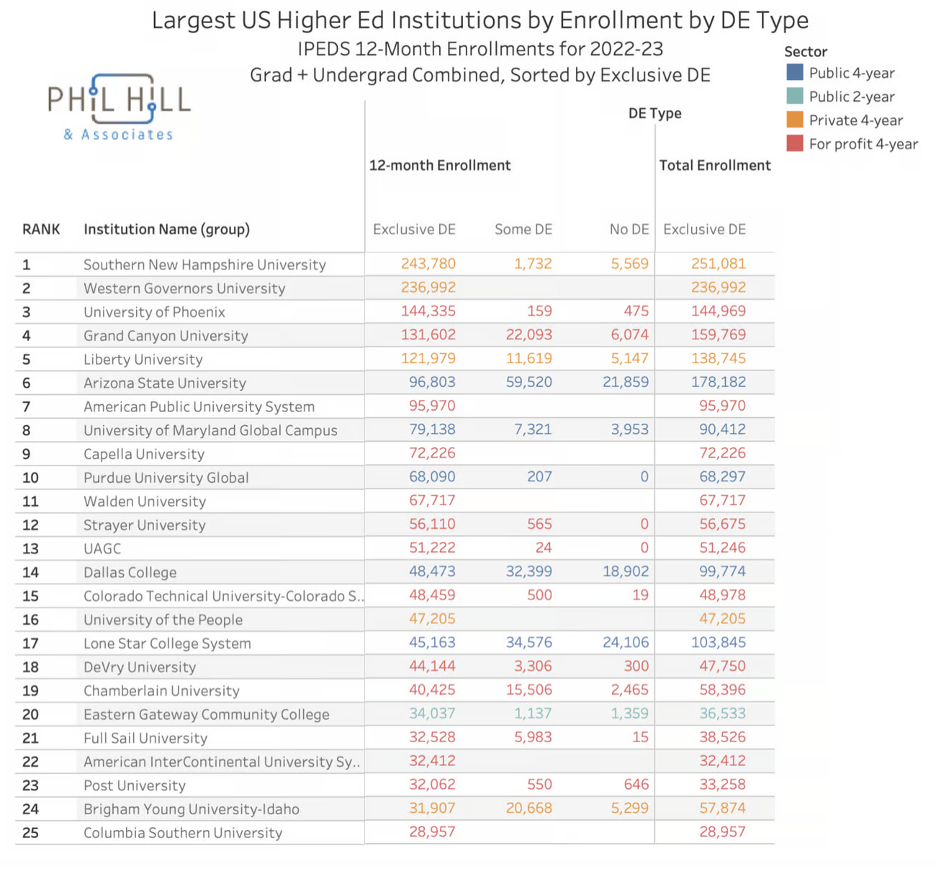

A review of the list of the largest US Higher Ed Institutions ranked by Distance Education (chart provided by Phil Hill and Associates that is appended below) indicates 12-month enrollments range from a low of 28,957 (Columbia Southern University) to a high of 243,780 (Southern New Hampshire University). Only the University of Louisville and Regent University in the list of the top 8 search results above are not listed in the top 25.

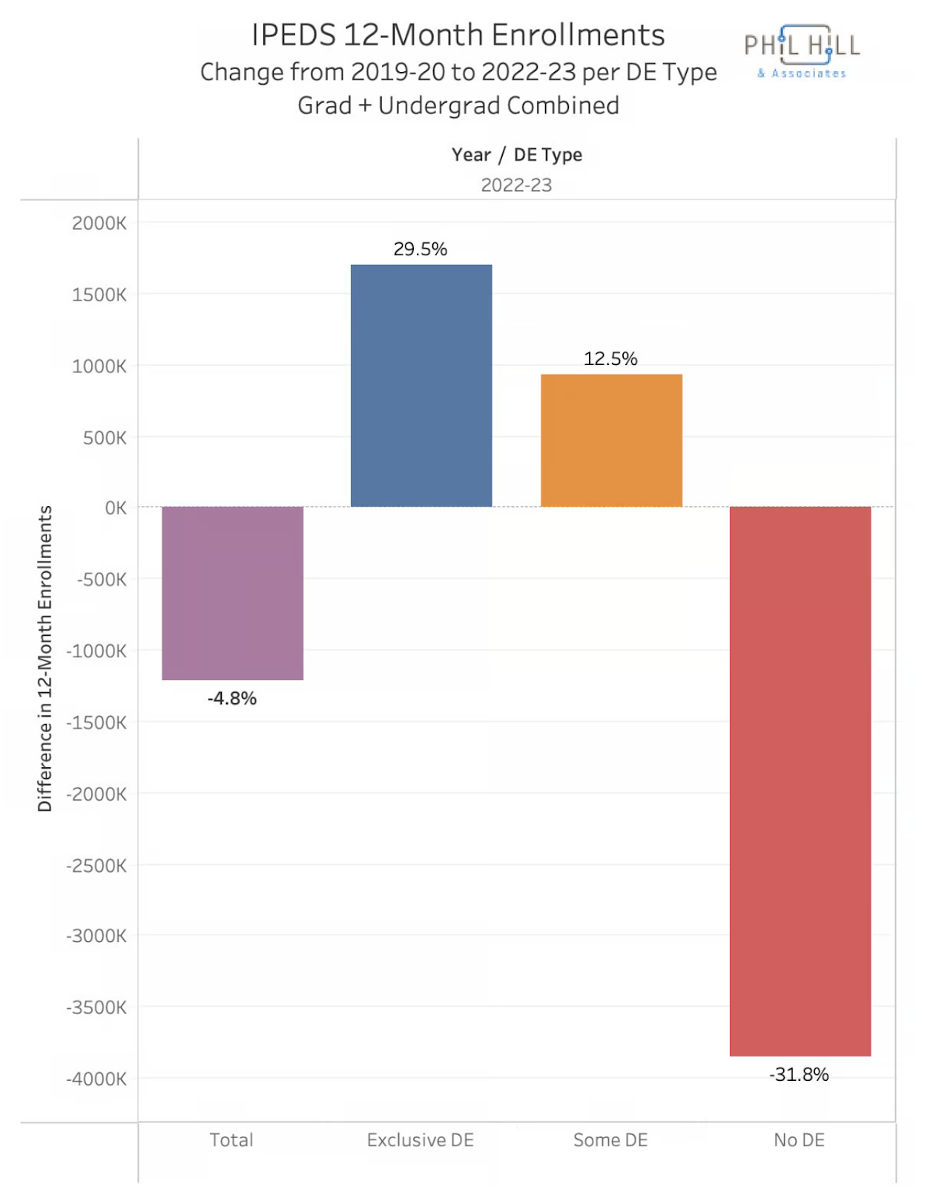

OnEdTech’s analysis indicates that during the three-year period from 2019-2022, combined undergrad and graduate enrollment growth in higher ed looked different depending on the type of instruction, with exclusively distance education programs exceeding all other learning formats in terms of growth at 29.5% (see chart below).

The “Exclusive DE” programs increased enrollments at a rate nearly 2.5 times the “Some DE” program. Institutions with no DE suffered a decline in enrollment of 31.8% during the same period.

Was the growth in total DE enrollments over the period due to the top institutions massively outspending the lower enrollment institutions? Unfortunately, that data wasn’t provided. However, spreading marketing and other online student support costs over 28,000+ students (the lowest enrollment of the top 25) is more cost-effective than spreading them over several hundred DE students.

The institutions with the largest enrollments distribute their marketing costs across multiple channels, including significant radio and TV advertising in specific markets. Depending on where you live, you may recognize the leaders in online enrollments as also leaders in local tv advertising.

The Ruffalo Noel Levitz 2022 survey cited earlier indicated that nearly half of all schools had established a group of recruiters to respond to online students’ program inquiries within three hours. Depending on the volume of inquiries, staffing that function is not cheap. Based on the percentage of students who enroll in the first online program to contact them, after-hours staffing is important (see RNL chart below).

During my years leading APUS, we recognized that our mission-driven low-cost tuition did not afford us the ability to spend the same money in marketing (i.e., $ marketing cost/per new student) as our online competition. We focused on generating lower-cost paid and organic lead generation instead of buying expensive traditional media ads. It takes time to build and publish organic content, including social media, on the internet so that the web crawlers operated by Google and the other search engines pick it up and weight it accordingly.

The bigger problem is what OnEdTech identified with their chart isolating the three-year changes in DE enrollment only, some DE, and no DE. Institutions with no DE experienced a 31.8% decline in undergrad and graduate enrollments. It’s likely that they’re adding or considering adding online programs to recapture some of their enrollment decline.

Colleges and universities with lower online enrollments are not going to be able to scale. If you cannot take advantage of the economics of scaling with your online programs, you are not going to lower your online prices regardless of the perception. It’s unlikely that institutions with low online enrollment will achieve the level of enrollment required to “make money and use it for whatever they want to make money for.”

Is Online Program Quality Defined by Lower Graduation Rates?

As part of his explanation of higher operating costs for online programs, Mr. Marcus writes that institutions need to provide “faculty who are available for office hours, online advisors and other resources exclusively to support online students, who tend to be less well prepared and get worse results than their in-person counterparts.”

Institutions with the largest online enrollments generally have open-enrollment admissions policies. While that doesn’t mean that 100% of all applicants are accepted, it generally means that their policies are not selective. Any applicant meeting a baseline standard will be admitted.

Are open enrollment admissions policies an indicator that those admitted are less prepared for college? It’s possible. At the same time, there may be some applicants who attended some college, did well, but dropped out for financial or other reasons. There could be a gap of 10 or more years since their last formal education. They may need refresher courses instead of remedial courses. Nonetheless, the odds are higher that someone who has just graduated from high school will be better prepared for college than someone whose last formal classes were a decade ago.

I published papers as well as blog articles that outline some of the reasons for lower persistence and graduation rates for students studying online. In a February 2012 blog article, I wrote about the perils of ignoring the online student at risk factors as well as student demographic characteristics and the characteristics of online student swirling.

Seven risk factors regarding persistence of adult students identified by Department of Education researchers are pertinent to many of the working adults enrolled in online courses:

- Being independent,

- Attending college part-time,

- Working full-time while enrolled,

- Having dependents,

- Being a single parent,

- Delaying entry to college,

- Not having a traditional high school diploma.

The eight different patterns of attendance for swirling students as identified by Alex McCormick are:

- Trial enrollment – students experimenting with another institution before formally transferring.

- Special program enrollment – students completing most of their coursework at their home institution but completing a special program elsewhere.

- Supplemental enrollment – students enrolling at another institution for one or more terms to supplement or accelerate their program (i.e., summer programs or taking a course at another institution because it is unavailable at the home institution).

- Rebounding enrollment – students alternating enrollment at two or more institutions.

- Concurrent enrollment – students taking courses at two institutions simultaneously.

- Consolidated enrollment – students who satisfy their home institution’s residency requirements, but a substantial number of their credits come from at least two other institutions.

- Serial transfer – students who make one or more intermediate transfers sequentially in order to complete a degree.

- Independent enrollment – students pursue work unrelated to their degree program and no credits are transferred.

A November 2014 blog article of mine discussed a research paper exploring swirling students that examined data uploaded from APUS enrollment records to the National Student Clearinghouse. Out of 49,000 students who matched, indicating that they earned credits at other institutions reporting to the Clearinghouse, 32,000 returned to APUS and 17,000 were permanent transfers.

I wrote that the traditional methods used to collect college student persistence data failed to collect multi-institutional attendance data as well as data related to stop-outs versus drop-outs. Subsequent DoE (Department of Education) reporting initiatives related to online course attendance have failed to capture many of the characteristics of online student attendance and persistence.

Nonetheless, if the graduation rate for online students is less than 50% (and my experience suggests that it is for most of the adult-serving institutions offering online courses), the inefficiency of having such a large percentage of students drop out will lead to higher costs as well. Based on experience, most online students drop out early (before completing five courses) instead of completing a year or two of courses and then dropping out.

While Mr. Marcus opts to play the tax status card and cites the “low graduation rates” at for-profit universities, he also cites the eight-year graduation rates for online students at the two largest non-profits, with Southern New Hampshire University at 37% and Western Governors University at 52%. I think it’s almost impossible to compare those rates with students attending traditional programs much less when the risk factors of enrolling part-time students who are working full-time are included.

Marcus writes that employers appear to remain reluctant to hire graduates of online programs. He cites a 2020 University of Louisville research paper that found applicants for jobs who listed an online degree were about half as likely to get a callback for the job. I read the study and noted that the researchers did not use applications from real people but instead 100 fictitious applicant profiles for 1,891 applications. The outcomes that he mentioned do not match with job outcomes for graduates of APUS during my tenure. It also does not match with grad school applications for our students who earned an online degree. I doubt that these outcomes match those of students graduating from the higher quality online programs.

Mr. Marcus also cites the lawsuits brought by students whose colleges sent them home during the outbreak of COVID-19 as evidence that consumers believe online education should cost less. Perhaps it does. At the same time, I recall that those lawsuits were more about receiving refunds for room and board and activities fees, not tuition.

According to Mr. Marcus, there are signs that the costs of online courses and programs may be declining. He notes the savings in room and board versus a program on campus. He writes about the low average cost of an education at Western Governors as well as Southern New Hampshire’s “slightly lower-than-average undergraduate price per credit hour.” At APUS, we are proud of continuing our mission of providing low cost tuition for more than two decades.

Also included in the reasons why costs for online programs may decrease are contract cancellations with online program managers (OPMs), whom he refers to as “for-profit middlemen.” As online courses and programs enter the mainstream, he writes that they will no longer require steep development costs. I would add to this by stating that with the availability of generative AI tools, online course development costs should decline by 75% or more.

Final Thoughts

Most people, I believe, compare their college educational experiences to their experiences in college. While online education has been around for the better part of three decades, its prominence has surged since 2019.

Despite the perception that the tuition for online courses should be lower than the tuition for on-campus programs, it’s not. I believe the reason for that is that most colleges and universities have not achieved the levels of online enrollment to cover the additional services required.

As far as outcomes, I believe that when online courses are developed and taught by qualified faculty, most differences in the course outcomes are attributable to student characteristics.

I was glad to see Eduventures’ Richard Garrett predict that online course enrollments will exceed on-ground course enrollments for the first time in 2025. Mr. Garrett does not mention that an expanded landscape of online course providers (traditional and non-traditional) could exacerbate the frequency of student swirling.

Institutions that want to minimize student swirling will need to enhance their online course and program offerings. One relatively inexpensive way to do this is through online course sharing. Consortial agreements for course sharing have been around for decades, and several platforms like Acadeum’s are available for their members to facilitate course sharing.

Another way to expand online course offerings is through a more rapid development cycle. Fortunately, several inexpensive AI tools are available that can decrease the time required to build quality online courses and minimize the cost of creating course learning artifacts such as videos.

Lastly, most employers I know hire people based on their skills and competencies. The institutions providing quality online courses have focused on specifying learning outcomes as well as tracking them. It’s another area where traditional colleges and universities must catch up.

In the earlier days of online programs, some graduates of online programs were impeded in their quest for a job that required the applicant to have a specialty-accredited degree and/or a professional license. Some of the specialty accreditors were slower to recognize online degrees than institutions were to develop them. I don’t think that’s an issue any longer, although I advise prospective students to verify the degree qualifications in advance.

As a proponent of affordable higher education, I believe that some institutions are providing lower-cost courses and programs. Because of their ability to scale, those institutions are likely to continue increasing their online enrollments.

Will the institutions with lower online enrollments catch up? I doubt it, but I look forward to watching the changing landscape.