After decades of touting the benefits of earning a graduate degree, I’m beginning to believe that more and more evidence touts the opposite.

In July 2021, Wall Street Journal (WSJ) reporters Melissa Korn and Andrea Fuller published an article titled “Financially Hobbled for Life: The Elite Master’s Degrees That Don’t Pay Off.”

The WSJ’s first article was followed by a second one a week later titled “Is a Graduate Degree Worth the Debt? Check It Here.” Those articles and the debt-to-earnings tool developed by the WSJ inspired me to write five articles about graduate debt and earnings that summer.

I was not surprised to see a recent headline in The Economist titled “Is Your Master’s Degree Useless?” The article states, “millions of people across the Northern Hemisphere will apply to do postgraduate study [in the coming months].” Why pursue a graduate degree? Insecurity was cited as a primary reason.

Based on The Economist’s next fact, there are many insecure people. Nearly 40% of U.S. workers with a bachelor’s degree also have a postgraduate credential. From 2011 to 2021, the number of postgraduate students in the U.S. increased by 9%, while undergraduates declined by 15%. Master’s degrees represented the growth in credentials.

Master’s degrees aren’t only big business in the U.S., however. The Economist writes that in the UK, colleges and universities issue four postgraduate degrees for every five undergraduate degrees earned. Over a 15-year period, the number of students enrolling in UK master’s degrees has increased by 60%.

One explanation for the UK’s growth in graduate programs is that the government caps undergraduate tuition and fees, and postgraduate tuition and fees are not. Enrolling more graduate students provides an economic boost.

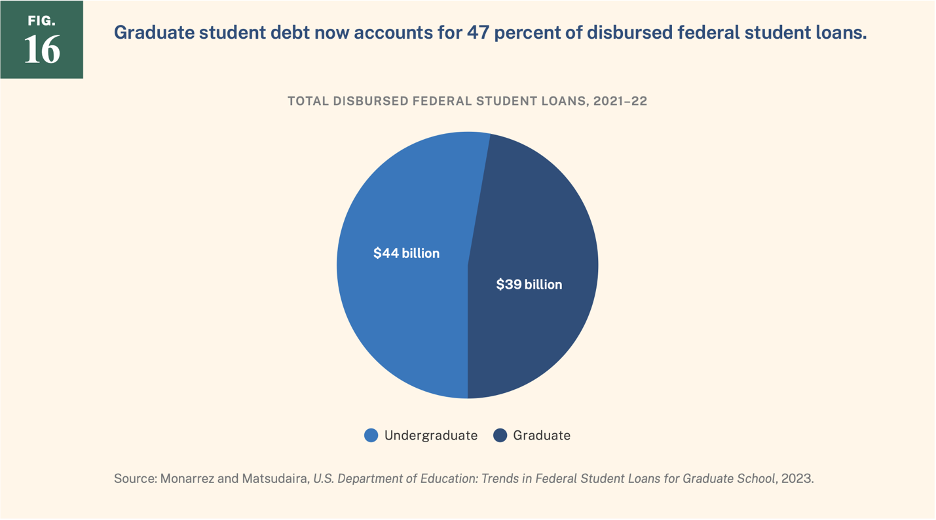

Citing a September 2024 Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce report titled Graduate Degrees: Risky and Unequal Paths to the Top, the reporters note that the cost of postgraduate degrees in the U.S. has more than tripled since 2000. Almost half of U.S. student loans are for postgraduates, even though they are only 17% of students.

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce

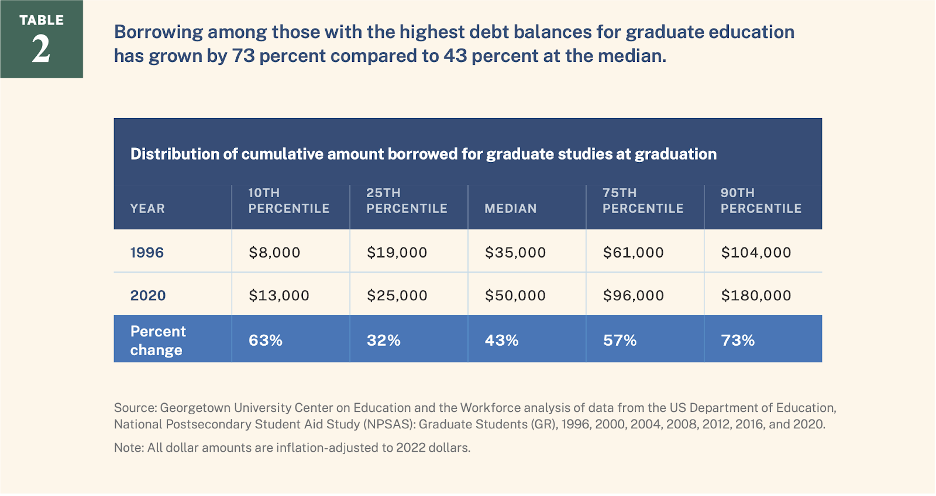

According to the same report, the median graduate student loan borrower accrues approximately $50,000 in debt, an increase of $16,000 from 2002. U.S. students are willing to borrow for a postgraduate degree because it increases their earnings on average by 18%.

The lion’s share of the growth in borrowing is concentrated in the top quartile of borrowers. According to CEW, between 1996 and 2020, the 75th percentile of borrowers grew from $61,000 to $96,000. The 25th percentile of borrowing grew from $19,000 to $25,000 over the same period. Growth at the 90th percentile was the highest. See Table 2 below.

The Economist notes that earnings “vary by subject and institution.” They add that graduate students are usually from wealthier families and earn better grades than undergrads. They probably would do well even without an additional credential. They add that looking at the real returns of a graduate degree requires matching outcomes with smart people who did not continue with graduate studies.

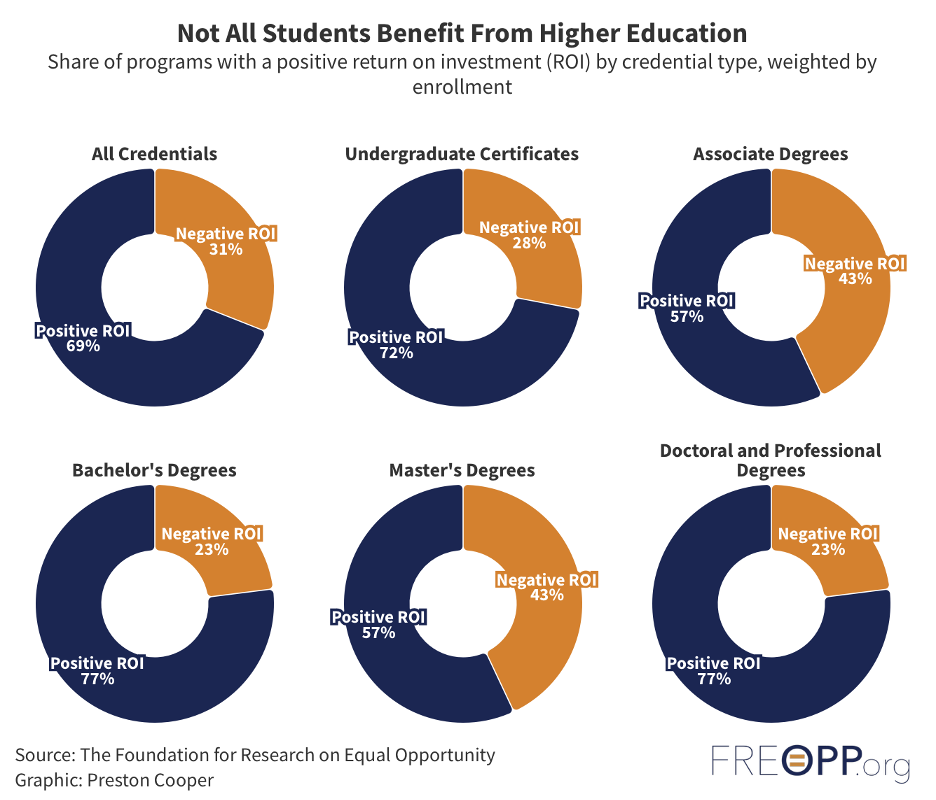

Is there a study that looks at the ROI of a graduate degree and considers the lost earnings of a grad student versus a bachelor’s recipient who entered the workforce and the other associated costs? The Economist cites the May 2024 FREOPP report titled Does College Pay Off? A Comprehensive Return on Investment Analysis.

I previously wrote about Preston Cooper’s 2023 FREOPP report, Why is Graduate School So Expensive? The May report continues that research using more recent data from the College Scorecard. Cooper and FREOPP introduce the concept of the Mobility Index, where the number of grads for each program is multiplied by the ROI.

Not all degrees provide students with a positive ROI. Cooper and FREOPP provide an overview by type of degree. Master’s and associate’s graduates have the highest percentage of negative ROI degree programs.

Furthermore, Cooper’s findings indicate that the median master’s degree delivers an ROI of $50,000. Yes, that’s not a typo. The median master’s degree ROI is $50,000. Master’s degrees in science, engineering, and nursing tend to have high ROIs, while master’s in the arts and humanities have low or negative ROIs.

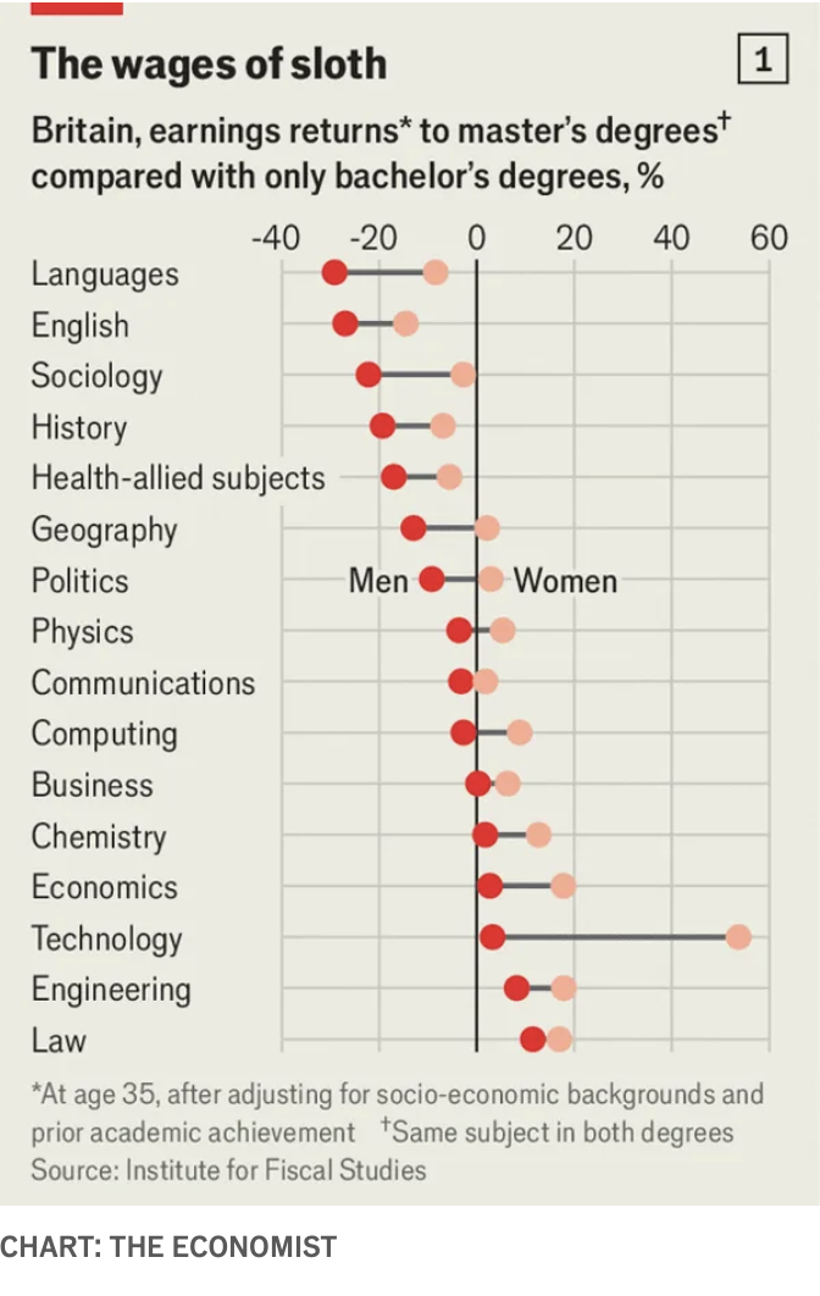

The Economist notes that American data is somewhat patchy compared to UK data. The reporters cite a 2020 UK report and analysis at the Institute for Fiscal Studies that uses a database linking the tax histories and educational achievements of millions of young adults.

The IFS study found that by age 35, master’s graduates earned no more than individuals with just a bachelor’s degree. The finding differed from previous research using less granular data.

Unsurprisingly, the data in the Georgetown CEW report, the FREOPP report, and the IFS report found that program area is the biggest single factor determining whether a master’s degree provides a positive ROI. Returns are generally highest for master’s in computer science and engineering. Master’s degree recipients in education tend to earn more because many U.S. school districts increase the pay of teachers who earn master’s degrees.

The Economist found it striking how large the negative returns were in some subjects. For example, British men who complete master’s degrees in politics earn 10% less at 35 than peers who complete the same undergraduate degree. A 20% hit to earnings was found for master’s degree recipients in history, and a 30% hit for English. See chart below.

Choice of institution matters, but less than is commonly assumed. In the U.S., costs range widely by university. However, there is no strong connection between the price of a master’s program and the amount its graduates earn. Quoting Preston Cooper of FREOPP, “Brand-name schools have realized that they can trade on their reputation to offer programs that look very prestigious on paper, but which don’t have outcomes that justify the hype.”

The single field with an exception to the brand name value differential is business. Grads from the top MBA programs make a lot more money than grads from non-distinguished MBA programs. The reason? These programs’ graduates acquire a fantastic network of future contacts from classmates and alumni.

Prospective applicants to master’s degree programs should not be the only ones concerned about many programs’ poor returns. The Economist writes that politicians in the UK and in the U.S. have been accused of pushing up costs.

In 2016, UK master’s students became eligible for government-backed loans with generous repayment terms. Since 2006, the U.S. has permitted graduate students to borrow whatever the university they attend charges. Thanks to these generous policies, the “easy money” has led to the inflation of the cost of a graduate program.

Neither government limits the loan programs to specific degree programs despite data analyses showing that certain degree programs have low or negative ROIs. The U.S. has applied ROI standards to for-profit universities, requiring them to eliminate low ROI programs, but not to the public and non-profit universities that enroll most students. The latter group will only have to issue warnings. In my opinion, the for-profit ROI standards should apply to all institutions.

The Economist quotes Bob Shireman of the Century Foundation (and former Deputy Secretary of Education in the Obama Administration) as stating that Americans from both sides of the political spectrum agree that graduate education is “a bit out of control.” That could make it easier to change the graduate loan system, assuming the new Trump Administration chooses to focus on reform instead of shaming institutions for their progressive policies.

Final Thoughts

Thankfully, the U.S. only conducts presidential elections every four years. With the flurry of proposed regulations coming out of the Department of Education, the FAFSA debacle, and the rhetoric from both parties, I missed the publication of the May FREOPP report and the September CEW report.

In a normal year, I might have written a separate article about each report. While the data is more current, the general outcomes and indicators are not much different. Many graduate degrees, particularly master’s degrees in the arts and humanities, do not provide the recipient with an ROI.

For people whose interest in a master’s degree may be related to a personal learning goal versus a career goal, I’d recommend attending a non-branded program, given that the data indicates no difference in earnings for elite programs other than the most prestigious MBA programs.

Learn the same content but pay less. That sounds like a smart consumer decision. Prospective undergraduate students are increasingly paying attention to affordability. Perhaps that same trend will migrate to graduate programs.

If Congress and the White House agree that graduate programs’ ROI is important, maybe they’ll restructure or eliminate the GradPLUS loan program with no caps. I have been an advocate of that for years. The Economist indicates that politicians have been part of the problem. Perhaps they can be part of the solution. That would be different and great.