I’ve been fortunate to spend a significant amount of time during my professional career in senior management roles in two industries, healthcare and higher education. The growth and expansion of both sectors can be traced to the year 1965 and the passage of major bills related to President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s Great Society.

On July 30, 1965, President Johnson signed the Social Security Amendments of 1965 into law. The amendments established Medicare, a health insurance program for people over 65, and Medicaid, a health insurance program for people with limited income. The programs were funded by a tax on employees and a matching payment from employers.

The Higher Education Act of 1965 (HEA) was signed into law on November 8, 1965. The law was intended “to strengthen the educational resources of our colleges and universities and to provide financial assistance for students in postsecondary and higher education.” Title IV of the Act covered financial assistance for students.

Long-Term Care

The notion of providing care for the poor and elderly was included in the Social Security Act of 1935 (SSA). The Act provided funding to the states for financial assistance for poor seniors. It specifically prohibited providing funding to anyone who lived in a public institution or poorhouse. Thus, an incentive was created for the private nursing home industry.

In 1950, an amendment to the SSA required payments for medical care to be made directly to nursing homes and not to the beneficiaries of that care. States were required to license nursing homes to establish their eligibility to participate in the Old Age Assistance Program.

When the SSA Amendments of 1965 were signed into law, Medicare focused on acute care only and did not provide coverage for long-term care. Medicaid required coverage of long-term care in institutions but not in the home. Overnight, the federal government and states became the largest payors for elder care, with 20 million people signing up for one or both programs in the first three years.

In 1968, amendments were passed to standardize nursing home regulations and withhold payments from nursing homes that did not meet those standards.

In 1974, SSA amendments authorized payments to the states for the provision of social services programs such as homemaker services, protective services, adult day care, nutrition services, and health support.

The Nursing Home Reform Act of 1987 (OBRA) required quality standards for nursing homes certified for Medicare and Medicaid. In 1987, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation initiated a pilot program in four states to encourage individuals to purchase long-term care insurance instead of relying on payments through the Medicaid program.

The Medicare Catastrophic Act of 1988 expanded skilled nursing benefits and established protections against spousal impoverishment from nursing home expenses (e.g., the non-institutionalized spouse was allowed to keep a jointly owned home rather than sell it to pay for nursing home care). The MCA of 1988 was repealed in 1989, but the spousal impoverishment rules were maintained.

The Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 provided federal funding to states to expand community-based care. It also lengthened the look-back period for the transfer of assets to qualify for nursing home Medicaid applications from 36 months to 60 months.

During my years in healthcare (1985-2002), I watched as nursing homes became more dependent on federal (Medicare) and state aid (Medicaid), and found it more difficult to attract long-term residents who were private pay.

The transition to a higher acuity Medicare population with higher daily room rates forced nursing homes to increase their daily room rates for private-pay residents. This led to a quicker spend down of available savings from private-pay residents. It also triggered the conversion of many former private-pay patients to the lower-paying Medicaid program as their savings were depleted.

Higher nursing home rates tied to patient acuity led to the creation and rapid development of the assisted living sector. Independent and assisted living facilities attracted most of the private pay population that used to reside in nursing homes because their daily room rates were not tied to acuity. The lower acuity assisted living facilities also provided an atmosphere more like a home than a place for sick people.

During these early years, assisted living facilities were not eligible to participate in Medicaid funding, so residents whose funds were depleted had to relocate to a skilled nursing facility participating in the Medicaid program.

When nursing homes’ private payor market shrank, the industry’s quality suffered. Its reliance on government funding subjected facilities to mandated staffing levels for acuity and swings in reimbursement based on changes in regulations or available funding. Increasing government regulations and nurse staffing challenges created a difficult environment to maintain compliance with those regulations. In addition, the loss of the lower acuity private pay residents increased the overall acuity for the facility and ramped up the exposure to regulations and staffing shortages.

Today, the average cost of a semi-private room in a nursing home is $314 per day, $9,555 per month, or $114,665 per year. There are approximately 15,000 skilled nursing facilities serving more than 1.2 million residents. The estimated median cost of an assisted living facility is $200 per day, $6,077 per month, or $72,924 per year.

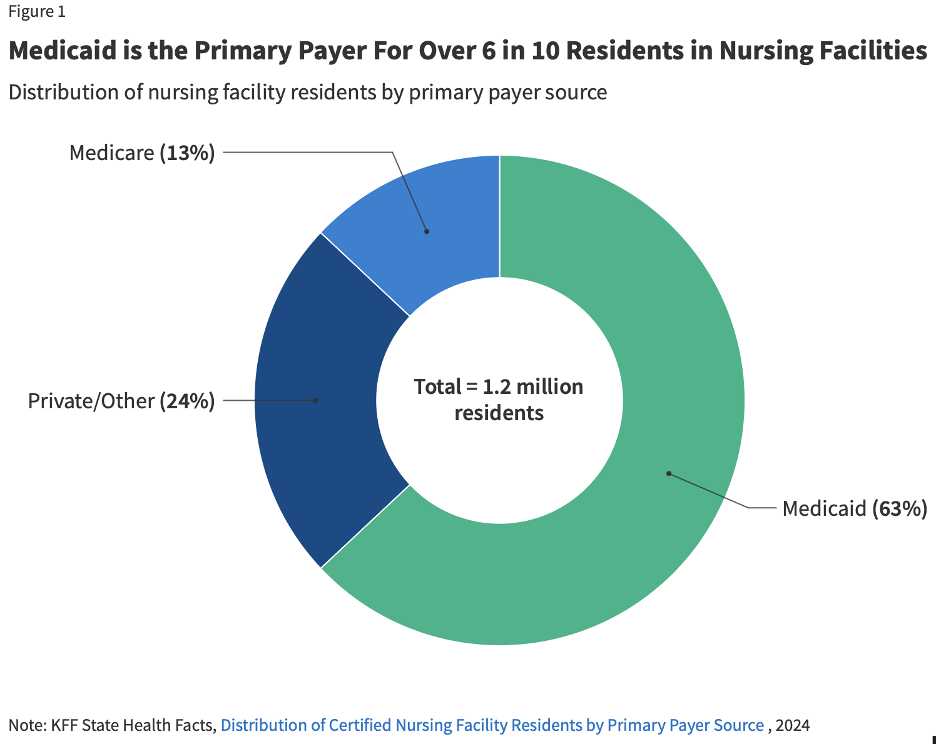

There are more than 32,000 assisted living communities serving approximately 1.2 million residents. Neither of these options is affordable for the median U.S. family income of $80,610 per year. Medicaid will cover 100% of nursing home costs for eligible low-income individuals. In fact, Medicaid is the primary payor for more than 60% of nursing home residents (see figure 1 below).

Higher Education

Over the years, I’ve written about the history of the federal government’s provision of aid for students to attend college. A short timeline synopsis includes:

- 1958 – National Defense Education Act (NDEA): Need-based, low-interest student loans of up to $1,000 per year were approved to encourage more students to attend college.

- 1965 – Higher Education Act (HEA): Title IV authorized need-based financial aid to students in the form of grants, loans, and work-study programs.

- 1968 – HEA first reauthorization: Basic Education Opportunity Grants were established as the lower of $1,000 or half of the sum of authorized aid including state grants.

- 1972 – HEA second reauthorization: Title IX amendment prohibiting sex discrimination was added. Proprietary schools were allowed to participate in Title IV programs.

- 1976 – HEA third reauthorization: The Basic Education Opportunity Grant ceiling was expanded from $1,400 to $1,800 per year, and the cap on graduate loans was increased from $10,000 to $15,000.

- 1980 – HEA fourth reauthorization: The Parent PLUS loan program was established to help high-asset parents (homeowners) create liquidity to pay their Expected Family Contribution (EFC).

- 1986 – HEA fifth reauthorization: Provisions were added to prevent students from borrowing additional loans under the programs if they defaulted on previously issued loans.

- 1992 – HEA sixth reauthorization: An unsubsidized version of student loans was established. Annual and aggregate loan caps were removed for all PLUS loan programs. Institutions enrolling more than 50% of students in correspondence programs were not allowed to participate in Title IV programs.

- 1993 – Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act: Direct Loan program authorized to begin in 1994. Income Contingent Repayment and other repayment and loan extension programs were established.

- 1998 – HEA seventh reauthorization: Distance Education Demonstration program was authorized.

- 2005 – Higher Education Amendments: Waivers were no longer required for institutions enrolling more than 50% of students online. The Federal Grad PLUS loan program was instituted with virtually no annual loan caps.

- 2008 – HEA eighth reauthorization: Net Price Calculators were required of all institutions participating in Title IV programs. The Department of Education was required to publish a list of the colleges with the largest annual tuition increases. An initiative to streamline the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) was announced.

- 2010 – Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act: Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) was phased out. New borrowers were allowed to cap the monthly amount they spent on loan repayment to 10% of their discretionary income. For new borrowers after 2014, loans would be forgiven for anyone who made timely payments for 20 years.

- 2025: The average cost of college in the U.S. for a full-time freshman is $38,270 per year. The average cost for an in-state student attending a public institution and living on campus is $27,146 per year. The average cost for a student attending a private institution and living on campus is $58,628 per year.

- 2025: Approximately 42.7 million borrowers owe $1.777 trillion as of March 16, 2025. The average federal student loan balance is $38,375. The average is skewed lower by the millions of borrowers who attended college for a few semesters and dropped out.

Will Students Seek Alternatives to Traditional Colleges and Universities?

When I consider the clamor about the federal financial aid system, the reliance on loans instead of grants to support higher tuition, and the pending changes that could disrupt many higher education institutions, it reminds me of the disruption that occurred in long-term care over the past four decades.

Thanks to an escalating cost of attending college that far exceeded the growth in families’ incomes, there are fewer full-pay families to support the 4,000+ colleges and universities in the U.S. How can anyone expect that students from families earning the median family income of $80,610 per year (or less than the median) can afford to pay even the in-state public institution average cost of $27,146 per year?

Federal student loans and state subsidies have provided foundational support for decades. However, state support is eroding due to fluctuations in income taxes and mandated costs such as K-12 education and Medicaid. Traditional college is affordable only for the highest-income families unless parents or their children are willing to borrow.

Unlike long-term care, where the assisted living sector developed, expanded, and captured most of the private pay (full-pay) residents, there is not a single class of alternative providers that are currently in a position to capture full-pay students from our existing colleges and universities. In lieu of formidable outside opponents, the sector finds itself offering generous tuition discounts (merit scholarships) to compete with peer institutions trying to attract a dwindling percentage of full-pay students.

The major difference between the two industries is that long-term care facilities must take care of an aging and increasingly sick population on-site. It’s not a scalable solution. Most older people (77%) continue to live at home until they can’t afford to or need constant medical care.

Higher ed institutions offer instruction on campus or online. The latter (online) is scalable. The former (campus-based) requires investment and reinvestment (maintenance) in expensive buildings. Annual room and board averages approximately $18,000 per year, more than half of the cost of attendance at public and state institutions. Online students may be living at home with their parents and may not have to pay them for room and board.

Online higher education continues to grow as in-person enrollments have declined (since the 2010 peak). The concentration of online enrollments in the 25 institutions enrolling the most online students has also increased. This bodes well for institutions that understand the needs of online students, but it doesn’t necessarily eliminate the potential disruption of alternative providers.

Why? Because only a handful of online higher education institutions rely on full-pay students. Online programs cost the same in many cases where the university operates on campus and online. Student loans and Pell grants support the online students just as they support the campus-based students.

Unlike long-term care, where the Medicaid program covers 100% of the cost for a qualified, low-income resident, higher education’s federally subsidized financial aid system covers only the lowest-cost colleges for low-income families, and even then, does not provide grants to cover the cost of room and board. Only the most elite colleges and universities cover nearly all the costs of attendance for their lowest-income students.

The data support the benefits of a post-secondary credential over a high school degree. However, the return on investment varies by degree and by cost of attendance. Enrollment in higher education declined from a peak of 21 million in 2010 to 18.1 million in the fall of 2023. The looming demographic shift will influence future enrollments unless a higher percentage of high school graduates enroll in college.

Will we see alternatives to traditional higher ed break through? If federal and state governments don’t subsidize those alternatives, I think it’s unlikely unless the benefits exceed the costs.

Will any existing providers restructure their business models by lowering costs and making their programs more affordable to lower-income families? I doubt it. While we’ve seen an expansion of no-tuition community college programs, those benefits have seldom covered all the costs of attending college.

The number of individuals taking a leap of faith that a college degree will lead to a great job has decreased. Most students (and their parents) are interested in the evidence that a college degree will lead to a job that more than covers their cost of attending college as well as their costs of living independently. These students either walk away from college or consider alternatives like trade schools without that evidence that college provides an ROI.

The costs of funding higher education have never been a statutorily mandated benefit like the costs of a K-12 education or providing Medicaid assistance to the poor. I don’t expect that to change. States will look for ways to adjust higher ed funding when budgets are tight. Unless more employers step in and provide postsecondary benefits, I don’t expect to see increases in future higher education enrollments. Well funded institutions will thrive. The rest will struggle to attract new student enrollments.