I’ve been thinking about how recently proposed federal distance education rules remind me of one of the beloved Harry Potter fantasy books. The similarity relates to the fifth novel, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, when Dolores Umbridge was appointed Defense Against the Dark Arts teacher by the Ministry of Magic.

Ms. Umbridge arrived at Hogwarts with an agenda to reject awareness of Voldemort. She refused to teach the students to defend themselves, so Harry, Ron, and Hermione formed Dumbledore’s Army to teach students magic defenses. Finding out that students learned self defense tactics invoked severe punishments from Ms. Umbridge.

During her Hogwarts tenure, Ms. Umbridge’s powers increased when the Minister for Magic appointed her High Inquisitor in an attempt to control the school. Her “Educational Decrees” were disliked by faculty and students alike and were dismissed when Dumbledore proved that Voldemort had returned and was reinstated as Headmaster.

Department of Education Rule-Making Session

In their most recent publication of proposed rule-making related to distance education, the U.S. Department of Education’s proposed regulations seemed to satisfy no one actually involved with distance education. This is not surprising given that none of their debt reduction proposals attempted to resolve the current problems of affordability and overborrowing.

Proponents of “consumer protection” ignored the facts that 49 of the 50 states and the District of Columbia voluntarily agreed to join the National Council for State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements (NC-SARA,) the organization created to reduce the paperwork required to license online courses and programs in states outside the institutions’ home bases.

The last time I checked, states that volunteer to join a reciprocity organization like NC-SARA are free to drop out.

Statements made by consumer protection advocates avoid acknowledging that student complaints are tracked and reported by NC-SARA until they are resolved. They also did not acknowledge that the institution and state are reported along with the nature of the complaint and in whose favor it was resolved.

Issues from NC-SARA’s Perspective

NC-SARA reported on the proposed changes discussed at the last negotiated-rulemaking meeting hosted by the Department of Education and noted that because an agreement was not reached, the Department could do anything it wanted (“negotiating in name only”). Key issues from NC-SARA’s perspective are:

- 500 Rule. If implemented, institutions would be required to obtain direct authorization from any participating state where the institution enrolls more than 500 students in each of the two most recently completed Title IV years.

- “Applicable State Laws” Related to Closure. This rule would authorize a state to enforce its own consumer protection laws related to closure. These include record retention, teach-out plans or agreements, and tuition recovery funds or surety bonds.

- NC-SARA Board membership. This rule stipulates that any governing body of state reciprocity agreements must be comprised solely of state regulatory and licensing bodies, enforcement agencies, and attorneys general offices. NC-SARA is a private 501c (3) with a diverse board of higher education experts.

An Online Provider’s Perspective of Distance Education Regulations

In 2008, I published a narrative on my blog about the American Public University System (APUS)’s efforts to seek licensure or a waiver of licensure for its online programs, beginning in 2006. Written by Dr. Russell Kitchner, the article described the “movement” of the regulatory landscape and the “imprecision” of the regulations that many states relied upon.

One of Dr. Kitchner’s points was that the U.S. Constitution stipulates that individual states are “the primary arbiters of policy and governance issues in education.” This includes laws governing colleges and universities, including those operating via distance education.

While the action that ultimately triggered the organization of SARA was the guidance for the Program Integrity regulations issued by the Department of Education in October of 2010, the April 20, 2011 Dear Colleague letter outlined Department expectations for state authorization.

At that time, I was a board member of the Presidents’ Forum which had initiated actions that ultimately led to the formation of SARA and NC-SARA, the organization that administers reporting and other requirements. At that time, we believed that the SARA initiative was needed particularly for small colleges attempting to expand their reach through online programs.

This is not the first time that the Department of Education has attempted to drastically reduce the effectiveness of SARA. In 2016, the Obama administration attempted to scuttle SARA after 47 states had ratified it. Fortunately, the regulations were issued in the waning days that year and were not implemented by the succeeding administration and Congress.

The Department of Education’s attempts to derail a voluntary reciprocity agreement are politically guided. Nothing else explains it unless the Department is generally opposed to providing access to millions of students through distance education.

Indications that the Department might be opposed to providing access to online education is also apparent in several other initiatives including:

- Certification Requirements added to the Program Participation Agreements (PPAs)

- The proposed virtual location for institutions to report data on students educated through distance education

- Proposed changes to third party servicer agreements specifically impacting Online Program Managers (OPMs).

Last June, I wrote about the notice of proposed rulemaking issued by the Department of Education on May 17, 2023. I provided a narrative of the work required for APUS to contact states and determine if licensure was required for its out-of-state online courses in the years prior to the launch of SARA.

I noted that the annual costs at APUS to maintain licensure or recognition in all 50 states exceeded $2 million and included three full-time staff plus assistance from internal and external counsel. That level of expenditures is out-of-reach for all but the largest online providers. I also noted that some states are not staffed to approve large online providers in less than a year.

Quality Online Courses

As a leader of an early provider of online courses and programs, I remember the strange looks that traditional educators would give me when I said that my university taught everyone online. Many early online providers focused on implementing best practices for building courses and teaching them as promulgated by Quality Matters and the Online Learning Consortium.

Focusing on best practices for designing courses, building them, and teaching them led to a focus on establishing and measuring learning outcomes. I believe the institutions with the largest number of enrolled online students know more about the learning outcomes of their students than academic leaders at traditional institutions.

Students who take online courses have a much easier ability to leave a college whose online courses do not meet their expectations in content, teaching, or quality than students who attend face-to-face programs. Because of those high expectations, the top providers are far more likely to offer engaging courses than traditional providers.

The Department of Education’s proposals ignore the current environment in online teaching and learning as well as its potential for providing an affordable education to those who need it the most. Based on my experiences with both modes of teaching, the Department might improve quality if it focused on regulating the quality of traditional courses.

Who’s On First?

The Department’s new regulations do not make sense. Over the next few months, as people and entities express their opinions about the proposed regulations, we’ll see which states are on which side of these proposals.

I find it interesting that the Department carved out a 500-student-per-state exception for regulation. That appears to be designed to reduce opposition to the proposal. Confirmation of this is the fact that NC-SARA’s website lists 57 SARA member institutions that had 500 or more students in multiple states in Fall 2021 and Fall 2022.

There are another 26 SARA member institutions that had more than 500 out-of-state students in 2021 and 2022 but in fewer than five states. There are more than 2,000 institutions that teach online courses. I stand by my statement that the Department appears to intend to reduce opposition by focusing on the largest institutions,

If there is a set of standards that 49 states have agreed to, including a framework for reporting and tracking student complaints, why should those standards be thrown away for institutions fortunate enough to have more than 500 out-of-state students?

Institutions with fewer than 500 out-of-state students should not ignore the political machinations behind this proposed regulation. The drafters want to change the governance of SARA as well. What safeguards are there to prevent the proposed 500-student minimum being lowered in future amendments to a single student?

Why should states be required to abandon their participation in a voluntary reciprocity agreement based on the whims of pursuing a single-minded objective to tear down the first nationwide reciprocity agreement implementing important standards for institutions offering distance education to abide by?

If the Department is interested in ensuring the strength of state authorization, student protections, and institutional accountability, why not just propose that an institution under some form of enforcement action by the Department – for example, a failing composite score or probation by its accreditor – may not participate in a reciprocity agreement?

The Landscape Prior to SARA

Prior to SARA, most states did not have separate standards for distance education programs. Colleges and universities seeking licensure were typically campus-based, teaching mostly traditional students in a face-to-face environment. The first movers in online education served non-traditional students, teaching asynchronously.

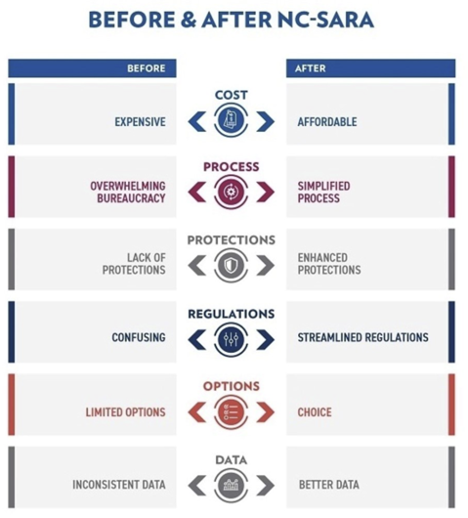

NC-SARA has a handy graphic that shows the differences between the “Before” state reciprocity era and the “After” NC-SARA era. I’ve appended it below.

NC-SARA also collects and shares data on student complaints quarterly. Here’s a link to their webpage explaining how students can file a complaint about an institution. If the complaint is not resolved, students can then file a complaint with their home state SARA affiliate.

Here’s a link to a dashboard where complaints can be viewed by year, by quarter, by institution, and by state. NC-SARA tracks each complaint until it is resolved.

Under the existing system of neg-reg hearings for proposed rulemaking, the Department of Education can implement whatever rules it wants if no one agrees. Those in favor of these proposed changes are choosing to ignore the evidence that the NC-SARA reciprocity agreements work.

The Ministry of Magic or Education?

Dolores Umbridge didn’t care what the students and faculty thought about her “Education Decrees.” She issued them one after the other with total disregard for their consequences. The decrees were based on her single-minded agenda to discredit Dumbledore and Harry Potter and consolidate power.

It appears that the Department of Education doesn’t care what institutions and state regulatory bodies think about their proposed state authorization for distance education regulations. They don’t care that the cauldron of state higher education regulations was never designed for online education and differ by state, sometimes dramatically.

Their proposals continue the myopic thinking of traditionalists that online education is inferior. Forcing the institutions that serve the largest number of online students to comply with a myriad of regulations leads to higher prices and fewer inefficiencies of scale. They don’t care.

There will be little reason for the 57 SARA institutions enrolling nearly 40 percent of online students to continue membership in SARA if they must return to the licensure and registration process that preceded the agreement’s effective date in early 2014. If the large institutions resign, the economics change for the smaller institutions.

It’s clear to me that the process used for proposed rulemaking by the Department of Education needs to change. However, Congress would have to initiate that through legislation. Congress has been unable to reach a consensus on a reauthorization of the Higher Education Act since 2008. Don’t expect a miracle any time soon.

Dolores’ counterpart in the Department of Education has an agenda. It’s unlikely her/his agenda will change unless most of the states that voluntarily signed the SARA agreement exercise their freedom of speech and complain about the proposed regulations. Based on the political environment, that may not make a difference.

Where’s Dumbledore’s Army?