I am a long-time reader and unabashed fan of The Economist. The UK-centric perspective of its business reporting provides an unfiltered (in my opinion) commentary on companies, trends, and events in the United States.

In its October 14 issue, The Economist issued a Special Report on the American Economy. The writer notes the Competitiveness Policy Council, a committee advising the President, declared in 1992 that the U.S. was condemned to slower growth than its industrial country competitors. Thanks to the rise of the internet, that forecast never happened.

More than 30 years later, some are painting a picture of potential economic decline for the U.S. China is depicted as the rising economic juggernaut. Presidential candidate Donald Trump declares that the economy is failing. Ordinary Americans, surveyed by Gallup, are anxious. Only 25% are satisfied with how things are going.

Regardless of some of these leading indicators, The Economist notes that America has grown faster than other big, rich countries since the early 1990s. In 1990, the U.S. represented approximately 40% of the overall GDP of the G7 group of countries. Today, it is approximately 50%.

On a per-person basis, U.S. economic output is approximately 40% higher than in Western Europe and Canada and 60% higher than in Japan. These percentage gaps are approximately twice as large as they were in 1990. Average wages in Mississippi, the poorest state in the U.S., are higher than the averages in the UK, Canada, and Germany.

Since 2020, U.S. growth has been three times the average for the other G7 countries. In the larger G20 group, the U.S. is the only country with output and employment above pre-pandemic numbers.

Why has the U.S. economy continued to be strong globally?

According to The Economist, U.S. companies benefit from scale. Additionally, the U.S. has a large, well-integrated job market. People can move to better-paying jobs and/or more productive sectors. Immigrants have provided growth and filled jobs that many Americans don’t want to.

Improvements in oil production have turned the U.S. into the world’s largest producer of oil and gas. Hosting the world’s deepest financial markets has made it easier to fund startups with equity instead of borrowing. The world’s dominant currency has greased the skids for global commerce. The U.S. has the world’s best universities, which attract top students.

The U.S.’s relaxed approach to business regulation has given high-tech companies room to grow. Regulators cite the government’s responses to the global financial crisis of 2007-2009 and the COVID-19 slowdown as positive interventions.

The U.S. is not without its problems. In 2023, U.S. life expectancy is 79, three years less than Western Europe. America’s lower life expectancy is due to obesity, opioids, guns, and unsafe roads.

Can the U.S. economic outperformance continue? The Economist sets the stage for several articles that comprise the rest of its report.

American Productivity Leads the World

The Economist applauds the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA) for its roles in inventing the internet, spearheading the popularity of the GPS, and developing the mRNA vaccines that reduced the global impact of COVID-19. The EU noted that DARPA’s backing of risky ideas with public capital has resulted in tech breakthroughs.

In 2024, the average U.S. worker will generate $171,000 in economic output versus $120,000 in the EU, $118,000 in the UK, and $96,000 in Japan. That’s a 70% increase in labor productivity in the U.S. since 1990 versus 46% in the UK, 29% in the EU, and 25% in Japan.

The gap looks similar on a per-hour basis. U.S. employee productivity per hour has increased 73% since 1990 versus 55% in the UK, 39% in the EU, and 55% in Japan.

Why has American productivity increased more than that of its global competitors? The Economist cites investment in capital as reason number one. Non-residential investment has comprised 17% of GDP in the U.S. since the mid-1990s. Excluding Israel and South Korea, the U.S. invests 3.5% of GDP in R&D, more than any other country.

The churn rate of U.S. companies, approximately 20% annually, is the second reason for productivity. European churn is closer to 15%. According to The Economist, it’s easier for old companies to close and for new companies to obtain startup funding. Churn allows the U.S. corporate base to keep evolving toward increased profitability.

In any given quarter, about 5% of U.S. workers change jobs. It takes a year for the same percentage to change in Italy. Americans are the most likely to relocate for jobs. Those who switch jobs tend to earn more than those who remain. The wage premium is notable for women, youth, and people with fewer skills.

Churn pushes workers, entrepreneurs, and capital toward more productive sectors. The Economist notes that the productivity gap between the U.S. and Europe is almost entirely due to the U.S.’s outperformance in a few digital-intensive economic segments, notably tech, finance, and professional services.

The U.S. tech superiority starts with its universities. Public support for research is robust. Equity investment capital is plentiful. Few regulatory hurdles hold back companies from scaling up.

Corporate concentration in the U.S. since the 1980’s is well documented. At the same time, proving that concentration has reached harmful levels is not easy. Over the last four decades, U.S. industries with rising concentration have been the most productive, and the top performers did not raise prices.

Based on a product-by-product analysis, concentration in the U.S. is declining. Corporate America is expanding into additional sectors, and tech giants are moving into conceptually new markets, like primary care and diagnostic services. The rise of concentration is more like competition in action than in decline.

The increasing number of applications using AI may increase productivity in the U.S. and abroad. Because the U.S. has been at the forefront of developing AI, it may receive a bigger boost than other countries. DARPA, cited by The Economist at the beginning, has funded and continues to fund many U.S. AI-related projects.

Has Faster Growth Increased Inequality in the U.S.?

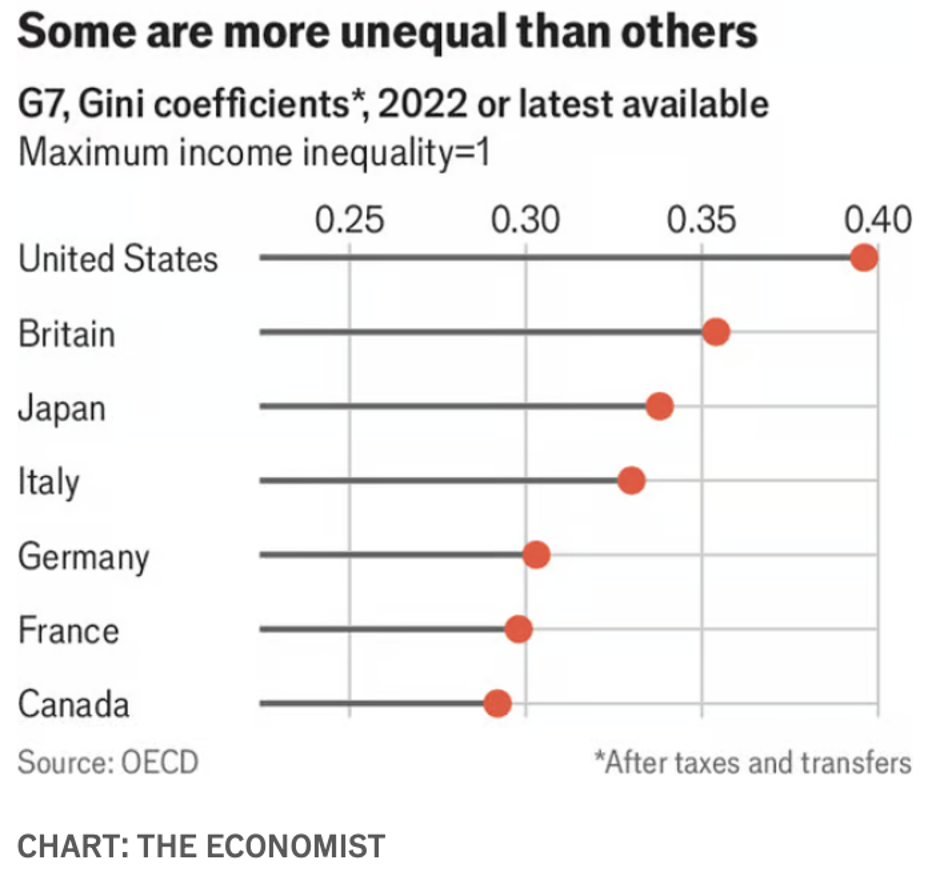

The U.S. leads the way as the most unequal big rich-world country according to The Economist. The chart below illustrates the contrast.

In the U.S., an annual income of $1 million places a household in the top 1% of earners. The UK only takes $250,000 to enter the top 1% of two-person households.

At the same time, lower-income workers in the U.S. have increased their incomes as well. Using fast-food workers as an example, The Economist notes that in 2019, a fast-food worker’s income was 25% higher than her counterparts in 2007. Since 1990, the bottom quintile’s after-tax income growth was 77%, the same as the highest quintile.

U.S. workers in the middle have seen lower increases in real income, which increased by 57% from 1990 to 2019. The Economist acknowledges that income inequality is only one type of inequality. Wealth inequality has risen since 1990 as well.

Shale Advances Influenced the U.S. Economic Boom

Thanks to advances in hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling during the 1990s, oil and gas production from shale formations in the U.S. surged. Today, the U.S. produces 13 million barrels of crude oil and 3 billion cubic meters of natural gas per day, more than any other country in the world.

Thanks to increased oil and gas production, the U.S. slowed its oil and gas imports and now exports more than it imports. In 2023, the U.S. netted an energy surplus of $65 billion.

While shale gas is more difficult to export, it has reduced U.S. domestic energy prices. This, in turn, has freed money for additional consumer consumption and corporate investment. Shale drilling rigs have declined over the past decade, but production has increased.

Perhaps more important than employment increases in the oil and gas industry, oil and gas produced from shale shielded the U.S. economy from the volatility of the global oil and gas market. For example, natural gas prices skyrocketed in Europe after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In the U.S., prices climbed slightly, but never more than 25% of the EU increase.

U.S. economic strength is highlighted by its impressive energy resources. Its confidence in capitalism enables U.S. investment in oil and gas wells. The U.S. allows individuals to own the minerals under their land. That ownership encouraged hundreds of companies to drill wells, determining quickly where the biggest oil and gas deposits were located

Critiques of the fracking process underlying shale oil and gas production are based on environmental issues. According to The Economist, those issues are superseded by the low energy required to generate oil and gas cleaner than coal extraction and generation.

The Economist cautions that the U.S. is at risk of landing into a fossil fuel trap thanks to its successful shale production. U.S. innovation and investments in clean energy are a distant second behind China. Shale fields will generate lower returns as the world decreases its reliance on oil. The U.S. needs to increase its investments in renewables.

The U.S. Stock Market Continues to Lead at the Top

The global outperformance of the U.S. stock market since 2000 has increased its share of global market capitalization to 61%. That percentage is not the all-time high (reached in the 1960s), but it is very close. More impressive is the fact that the U.S. is less economically dominant than it was 50 years ago.

An investor in the U.S. stock market received an annual return of 7% in the 20th century versus a 4.9% annual return outside the U.S. This growth is more impressive when you factor in the size of the U.S. stock market versus its competitors. The U.S. market trades at 24 times forward earnings versus 14 in the EU and 22 in Japan.

The U.S. market is weighted more toward growth stocks valued at higher multiples. These growth stocks include the seven tech giants, almost all of which are investing heavily in AI. U.S. companies tend to reinvest more of their profits, increasing growth expectations.

U.S. venture capital investments comprise 45% of global VC investments. This attracts companies located outside the U.S. to relocate to the U.S. due to its attractive investment opportunities.

U.S. equity markets have only been displaced at the top once since 1902. That occurred in 1989-90 when Japan rose briefly to the top. Japan is still number two, but its market is only 10% the size of the U.S. market.

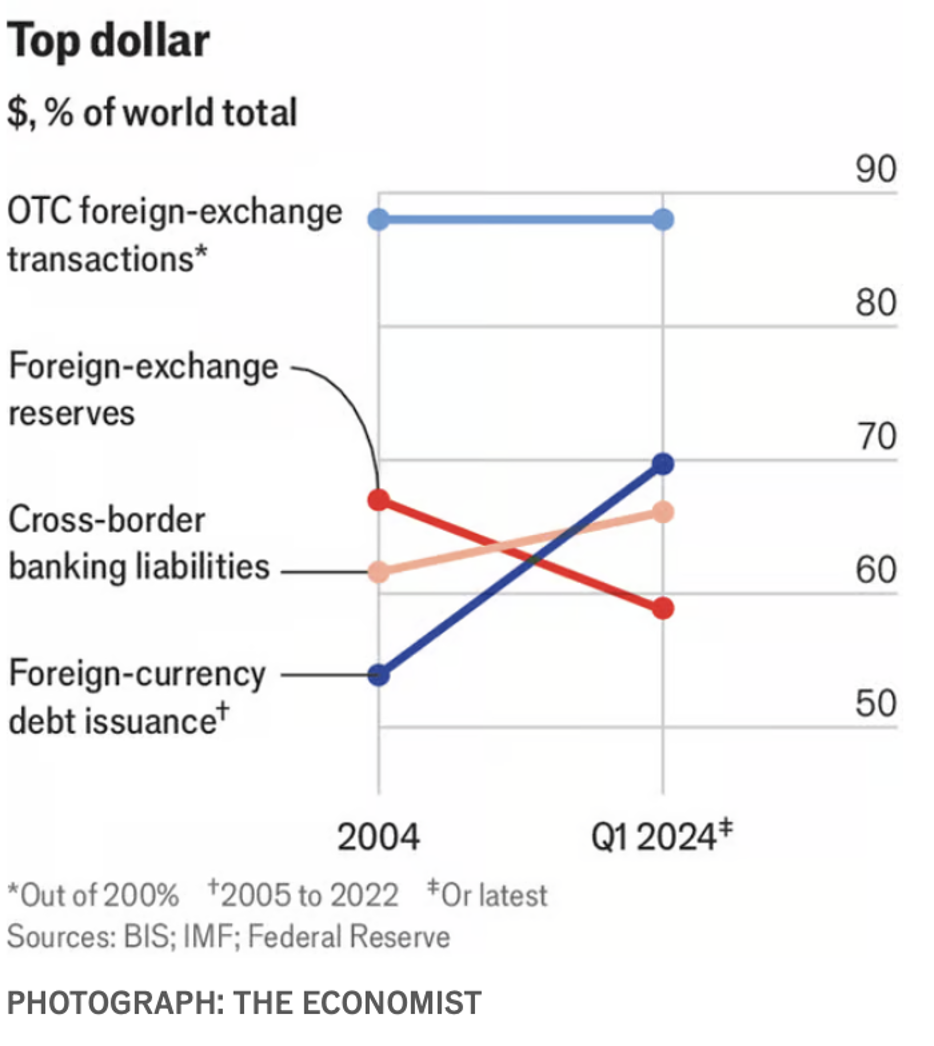

The Dollar Continues to Dominate Global Currency Exchanges

The Economist reports that the dollar is the currency of choice for trade, cross-border investment, and foreign exchange transactions. At the same time, its dominance in reserve holdings and trade-invoicing has declined (see chart below).

The global appeal of the dollar appears to give the U.S. an “endless supply of credit and the power to cripple foreign financial entities with sanctions.” Based on its market strength, the U.S. accounts for more than 25% of the world’s economy.

China has spent the past ten years attempting to do more business in its currency, the yuan. Somewhere between 25% and 30% of China’s goods and services trade is conducted in its currency. Nearly 75% of dollar holdings are held by foreign governments with a military alliance with the U.S.

Two-thirds of global trade involves dollars. Economists believe this would seldom change because rich countries are mostly U.S. allies. If these allies were excluded, only 25% of global trade would “be available” for other currencies. Almost 75% of that trade is between emerging markets other than China.

China’s authoritarian system makes investors hesitate to hold the yuan. The EU lacks assets on the scale of the U.S. Treasury. The U.S. combination of legal stability, liquid markets, and open capital accounts provides investors with more liquidity and less risk.

Thanks to the demand for the dollar, U.S. companies can borrow more cheaply. U.S. net public debts equal 99% of its GDP. The U.S. continues to run a deficit worth 7% of GDP. U.S. assets comprise more than 25% of the global investment in financial instruments. Politicians considering changing the U.S.’s reserve currency role would lose these benefits.

Could Politics Stop the U.S. Economy?

The Economist writes, “despite nearly constant political rancour and division over the past few decades, the U.S.’s growth trajectory has remained impressive.” The biggest potential obstacle is political brinksmanship.

The U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio has tripled since the 2007 global financial crisis to 99%. The U.S. Congressional Budget Office forecasts that it will increase to 160% over the next 30 years (Japan’s is currently 157%). Unfortunately, this lets politicians off the hook from making unpopular decisions to reduce deficits.

The U.S. drift toward extreme politics poses other dangers to its economy. Reducing immigrants (as threatened by Donald Trump), increasing tariffs (another Trump promise), and increasing regulation on tech companies (a Kamala Harris posture) are not conducive to economic growth.

The Economist notes many reasons to be optimistic about the U.S. economic future. Politically, the U.S. usually self-corrects its excesses. Its politicians have worked together across the aisle in moments of great crisis. If a global trade war erupted, its size and heterogeneity would protect it. Smaller economies would be the biggest losers.

Again, The Economist notes that “the foundations of American productivity – a giant, competitive domestic market, many of the world’s best universities and the sanctity of the rule of law – are firmly entrenched.” They will endure regardless of who takes the White House.

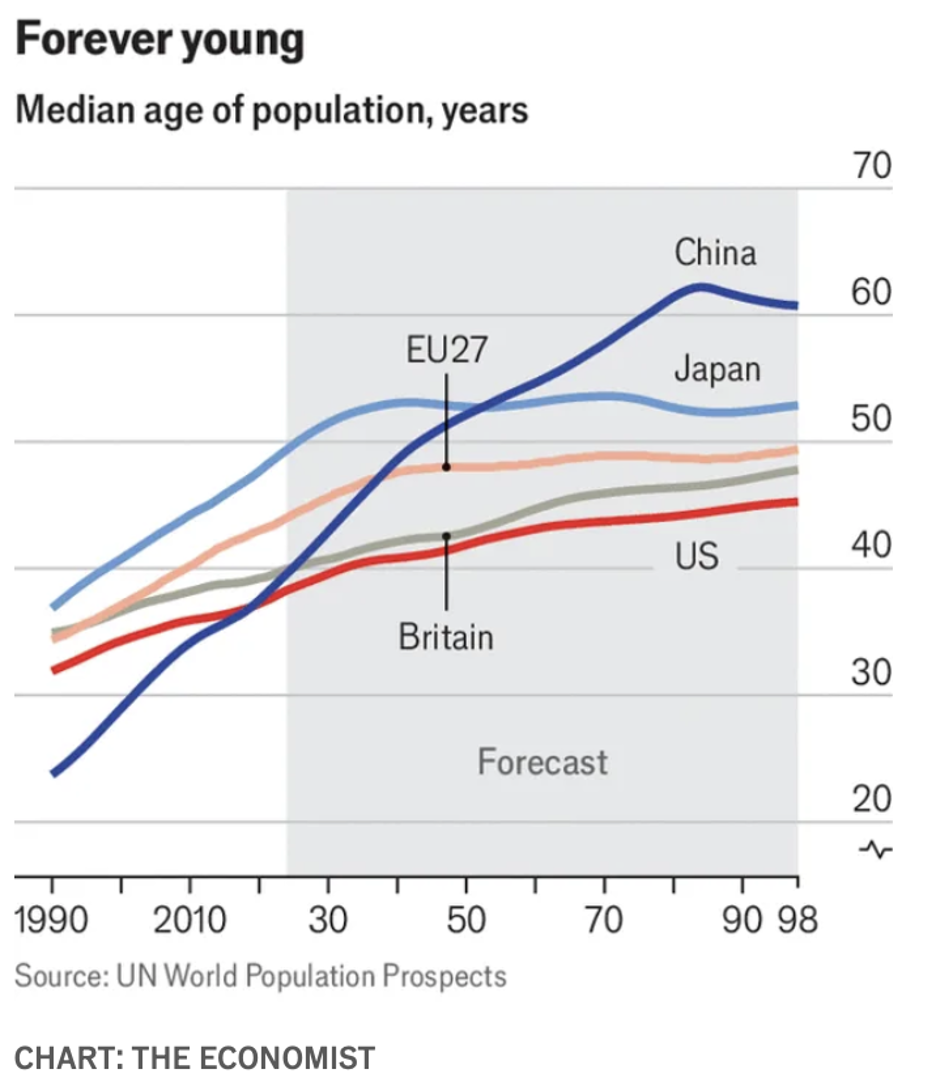

U.S. demographics are healthier than many others. Although the U.S. population is getting older, it has a higher fertility rate and a better ability to absorb immigrants. The U.S. accounts for 4% of the world’s population today; by 2100, it will be about the same. In relative terms, it will be a younger country.

See the chart below.

The Economist points out that all these factors indicate ongoing economic outperformance. The greatest potential impediment will be U.S. politics.

A Few Additional Thoughts

It’s been a while since I’ve read (or likely seen) a U.S. newsperson report about the good things happening in our economy. In an election year, it’s always worse as the ads and news seem to accentuate the faults in our economy and our lives that the actions or inactions of the other political party have caused.

I’m not a fan of illegal immigration, but I believe strongly in reaching a political compromise that allows a steady and predictable flow of immigrants who will positively contribute to our society. The Economist states that immigrants contribute to our economic growth. Let’s find a way to control the flow rationally and in a win-win manner for everyone.

I enjoyed reading the positive compliments about U.S. universities. At the same time, I worry about our universities. Since 2020, the political rancor emanating from campuses appears to be at a level equal to or exceeding that of our politicians. I applaud those campus leaders who have moderated the discussions.

However, campus political unrest is not our biggest problem as I see it. For years, I have written about the college affordability crisis. It is not getting better. State funding comprises the bulk of our subsidies, and few states are stepping up to ease the burden on their citizens.

U.S. higher education has changed more in the past three decades than in the three previous centuries. Because of artificial intelligence’s impact on learning and the workforce, it must evolve quicker and faster to address the affordability issue.

The Economist cites DARPA’s positive investments in technology over the years, which have accelerated the development and adoption of the Internet, GPS, and AI. Thankfully, our government and private sectors are willing to make these large bets. Our K-12 schools, colleges, and universities need to keep up with the pace of innovation.

If our colleges and universities optimize for the future of work, they’ll attract the best students (domestically and globally). Sadly, there is a huge gap between the top students moving from our K-12 system to higher education and the bottom half of K-12 students. States that are unable to maintain a public school system that maximizes learning for all students will fall behind economically.

The Economist cites the EU’s tendency to regulate technology innovation and growth as one of the major reasons that the less-regulated U.S. economy has continued to outperform countries in Europe. Throwing up roadblocks to innovation for no reason other than to make a nice political soundbite is not what we need to continue our growth.

The writers at The Economist conclude that they are optimists, willing to bet on the U.S. continuing to lead the world in economic growth. I hope we all work to make that bet successful.