Sometime in the mid-1990’s, I became familiar with the concept of tuition discounting. I was not yet working in higher education, but served on an independent school board with an economist who worked in higher education. When she described the practice of tuition discounting by colleges, she recommended that I read economist David Breneman’s book.

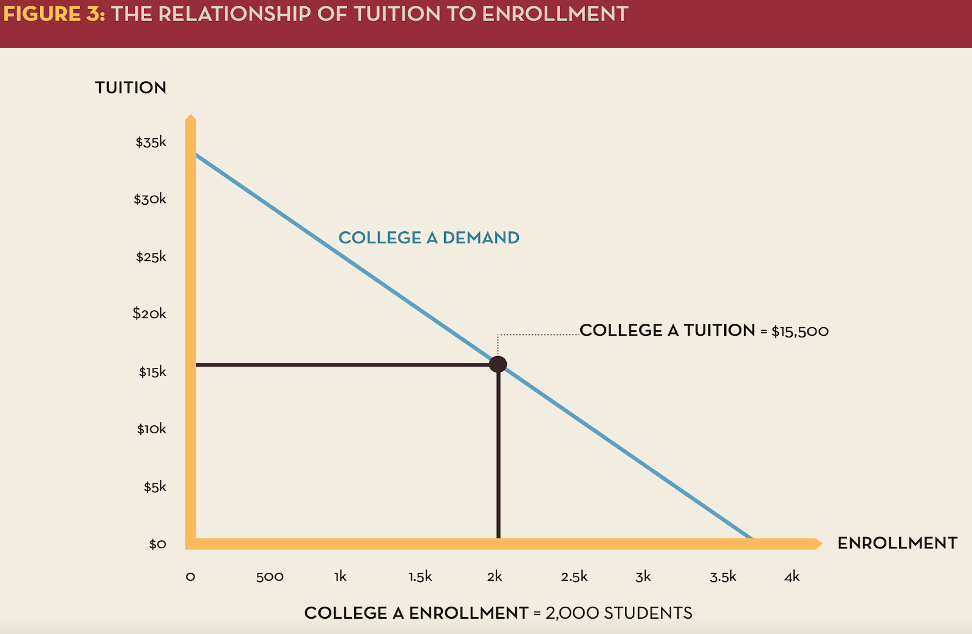

In many of my speeches about the evolution of higher education, I frequently mention Liberal Arts Colleges: Thriving, Surviving, or Endangered as the seminal publication describing why small colleges artificially inflate their tuition and use the increase to fund merit scholarships to targeted students. Breneman’s illustration of the relationship between tuition and enrollment is shown below.

The chart represents a simple supply-and-demand line. The higher the tuition, the lower the enrollment, and vice versa. College A should be able to achieve its targeted enrollment of 2,000 students if it prices its tuition at $15,500. If tuition was inflated but discounted through the offer of merit scholarships, colleges could achieve their targeted enrollments and student academic profiles.

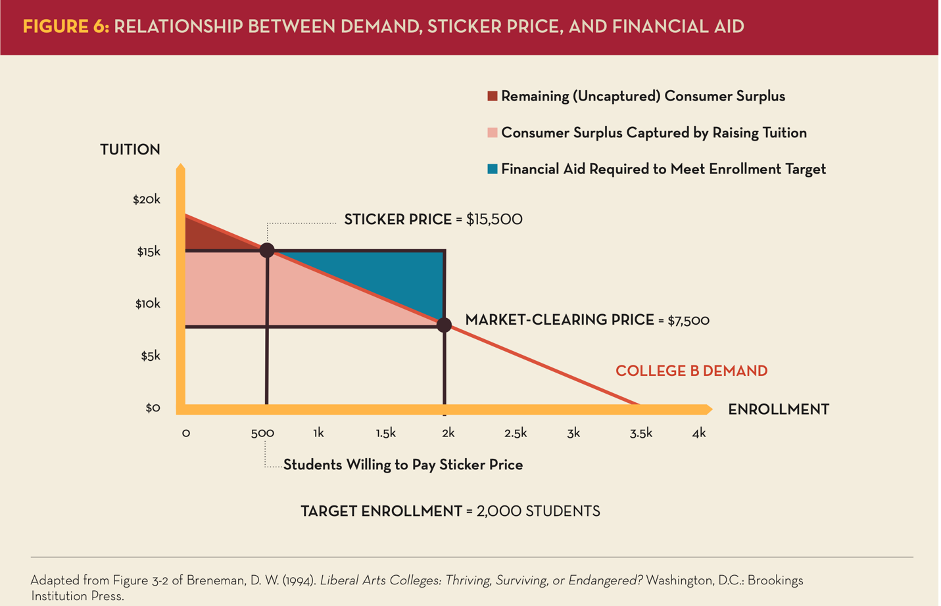

P. Jesse Rine wrote an excellent whitepaper explaining Breneman’s logic and how it could lead to disastrous consequences. A chart like the one above was used to portray the amount of financial aid needed to attract students from a list price demand to increased demand at a lower price of a 52% tuition discount for College B.

Breneman warned in his book that a delicate balancing act was required to keep the tuition discount rate at a reasonable percentage. His warning back in 1994 looks prescient today.

Tuition Sticker Shock

Fast-forward 30 years since Breneman’s book was published, and tuition discounting is widespread. On July 22, 2024, in a Higher Ed Dive article titled “Sticker shock: A look at the complicated world of tuition pricing,” Ben Unglesbee provides one of the more recent updates and insights into the current status of tuition discounting at colleges.

Unglesbee interviewed Phillip Levine, an economist at Wellesley College and author of the book A Problem of Fit: How the Complexity of College Pricing Hurts Students – and Universities. Levine stated that tuition discounting is “not good for anybody. It’s not good for the students. And it’s not good for the institutions…but there’s no way to get out of it.”

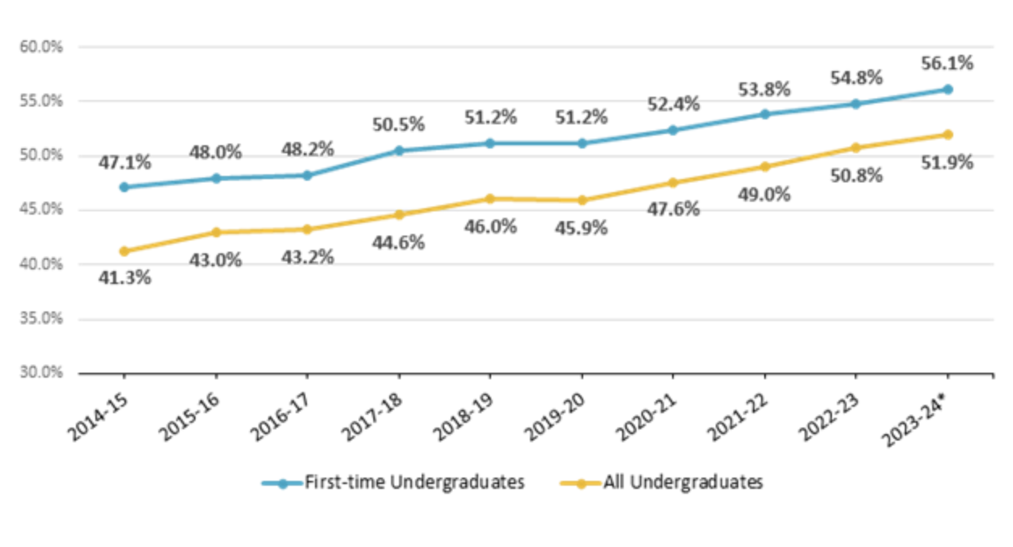

Unglesbee reported that the annual study from the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO) reported a new high of 56.1% for first-time, full-time students at private, nonprofit colleges in 2023-24. The discount rate for all undergraduates increased to 51.9%. See the NACUBO chart below, reporting a 10-year trend.

The study found that 83% of undergraduates received institutional grants (aka discounts) in 2023-24. What is unsaid about this statistic is that it means that only 17% of undergraduates are full-pay students.

According to Levine’s research, the difference between the net price of $24,600 and the sticker price in 2019-20 for a student from a family with an annual income of $50,000 was $46,300. The net price in 2019-20 for a student from a family with an annual income of $250,000 was $52,900, meaning that the higher-income student still received a scholarship of $18,000.

One of Levine’s statements echoed my feelings about the current price of college. “The number that bothers me the most is the increasing costs for the low-income kids,” Levine said. “If you’re making $50,000 or under, you still have to come up with almost $20,000, which is essentially impossible.”

Market Pressures Drive Grants

Another economist, Dr. Lucie Lapovsky, was interviewed. She stated that schools that give out a lot of merit aid are in a very competitive market. The following quote reminded me of a premise from Breneman’s book: “A school wants a certain number of students at a certain academic level or a certain set of criteria, and they want a certain net tuition. Unfortunately, it is very hard to control all of those variables or even many of them.”

Dr. Lapovsky stated that colleges often use outside firms to calculate the statistical models used to create a leveraging matrix for admissions offices. The models provide the probability that a student with specific characteristics will enroll if the college offers $X in aid.

What the calculations can’t do is predict with certainty that students will accept the admissions offers. That is where the calculations for the awards can go awry. If a school falls short of its targets, it can be forced to increase its awards to convince applicants to enroll.

Psychological Marketing Strategy

Among the experts that Unglesbee interviewed, most said that the high sticker price signals quality. “Most parents would rather say ‘my kid got a $40,000 scholarship to an $80,000 school’ than just pay the $40,000.” High-dollar value scholarship offers can be an important tool to entice students to accept their admission offer.

High sticker prices can also turn some prospective students away from applying, causing sticker shock among the students and their families.

Should Colleges Reset Tuitions?

With confusion about the difference between the sticker price and the net price after grants and scholarships, Unglesbee asked if colleges should adjust their sticker prices. Levine stated that the straightforward way to adjust prices would be for colleges to work together. Unfortunately, that tactic violates antitrust laws.

A legal way to adjust prices is for colleges to individually adjust their sticker price to a number closer to their net price. Unglesbee cites a paper written by James D. Ward and Daniel Corral that found short-term evidence that tuition resets benefit enrollments but only minimal evidence that tuition resets increase enrollment over the long run.

Stacey Linderman, a consultant who works with NACUBO, stated that resets succeed most often at the program level. Families understand that “the price of an engineering degree is going to be very different than a business degree and be very different than a liberal arts degree.”

Should Colleges Deepen the Discount?

Lastly, Unglesbee asked Dr. Lapovsky for her thoughts about schools deepening the tuition discount to increase student enrollments. Dr. Lapovsky said that deepening the discount typically leads to an enrollment decline. Furthermore, colleges can control their prices and discounts but can’t control demand for their product.

Lastly, Dr. Lapovsky stated the obvious. “We have too many schools. So they’re all fighting for more and more students.”

An Increasing Tuition Discount Is Not Good News

I wrote about the NACUBO Tuition Discounting Study in 2021. At that time, the discount rate for first-time, full-time undergraduates (freshmen) was 53.9%, a record. A scant three years later, the number has increased to 56.1%.

A point that I noted about the NACUBO survey is that the number they report is an average, meaning that colleges have numbers higher than the current 56.1% for freshmen and colleges have averages less than 56.1%.

Years ago, when I began tracking discount rates, I remember someone telling me that the discount rate is only a problem when it exceeds 50%. It’s been more than 50% for several years now. There are colleges where 100% of the freshman class receives institutional aid. I know one where the first-time, full-time undergraduate discount is over 70%. A friend of mine is a graduate and told me that the only reason the school is not in bankruptcy is its large endowment.

Robert Zemsky, Susan Shaman, and Susan Campbell Baldridge published their book, The College Stress Test, in 2020 to provide a guide indicating whether or not a college was in trouble. One of the two financial variables used in the Stress Test was the college’s market price, a variable very similar to the average net price (tuition minus institutional grants).

The market price for a college or university over an eight-year period is charted. A declining average market price indicates the institution’s difficulty recruiting a new class at the same market price as the previous year.

I suspect that more than a few of the private colleges that have announced expense cuts or closures over the past year have experienced lower enrollments even after increasing their tuition discounts to attract more students.

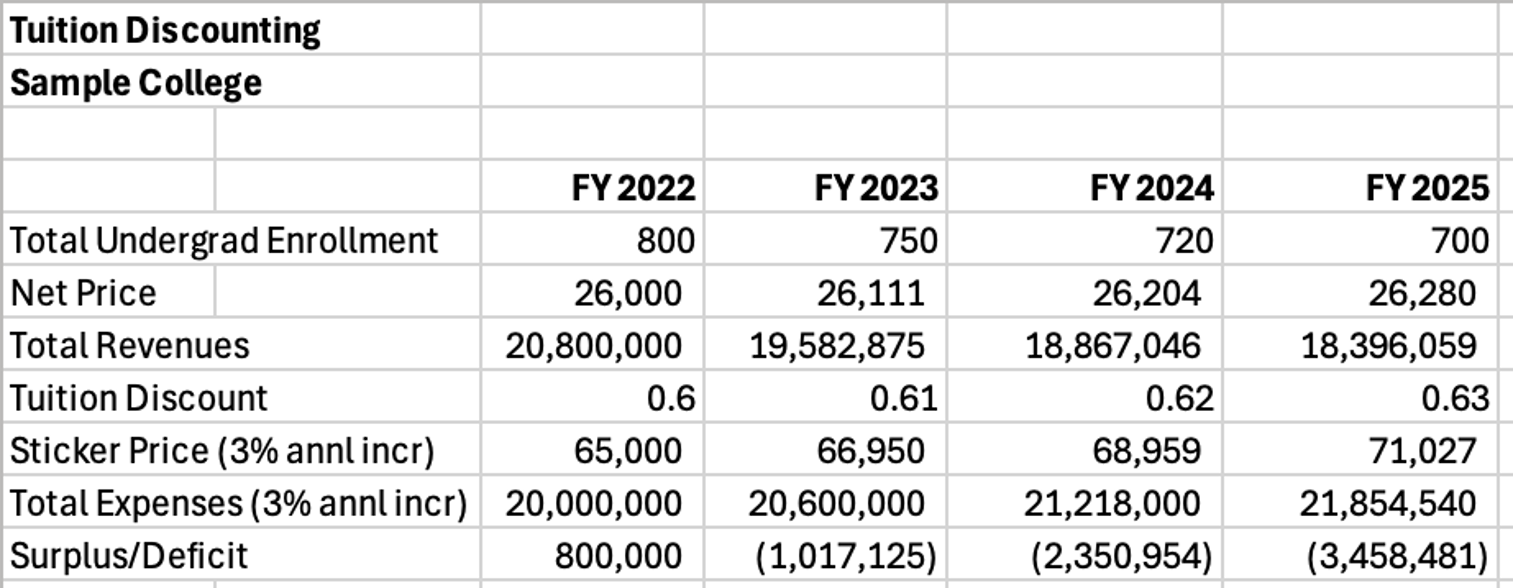

In the table below, I created an example of a small college (starting enrollment of 800) and how enrollment declines that lead to very small adjustments in tuition discounts and do not lead to enrollment increases can be financially disastrous.

Without an endowment to cover these losses, this college is in serious trouble.

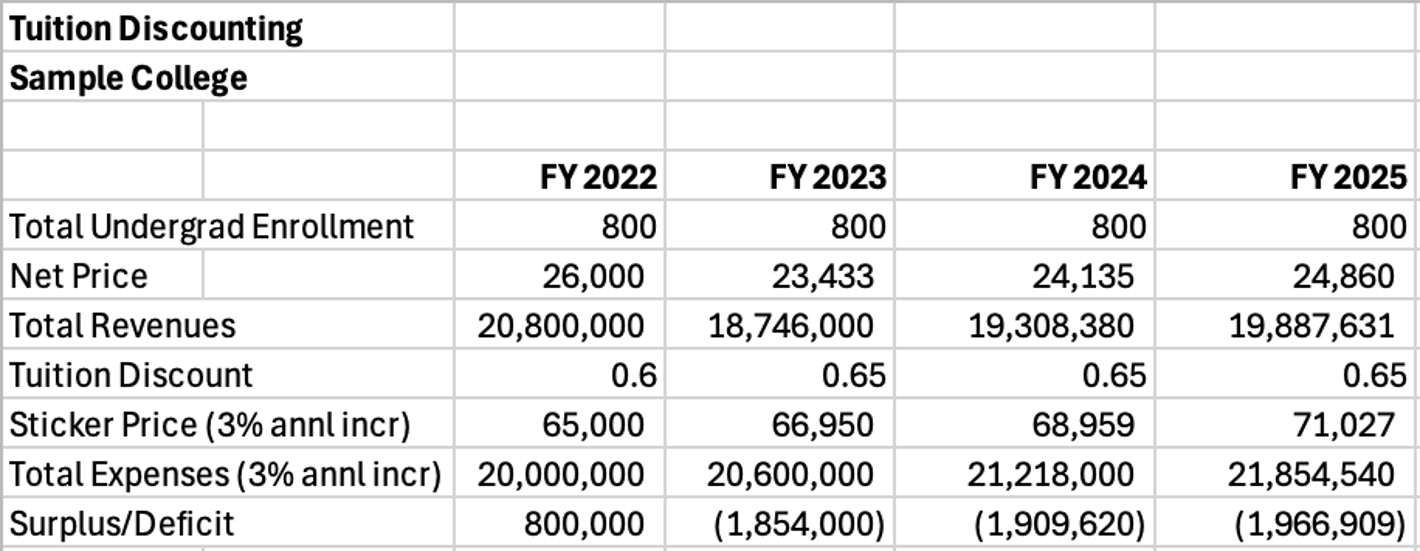

If the college increases its discount rate and only maintains enrollment, the outcome is not good either because there is less cash flow to cover expenses that continue to increase at 3% per year. See Table below.

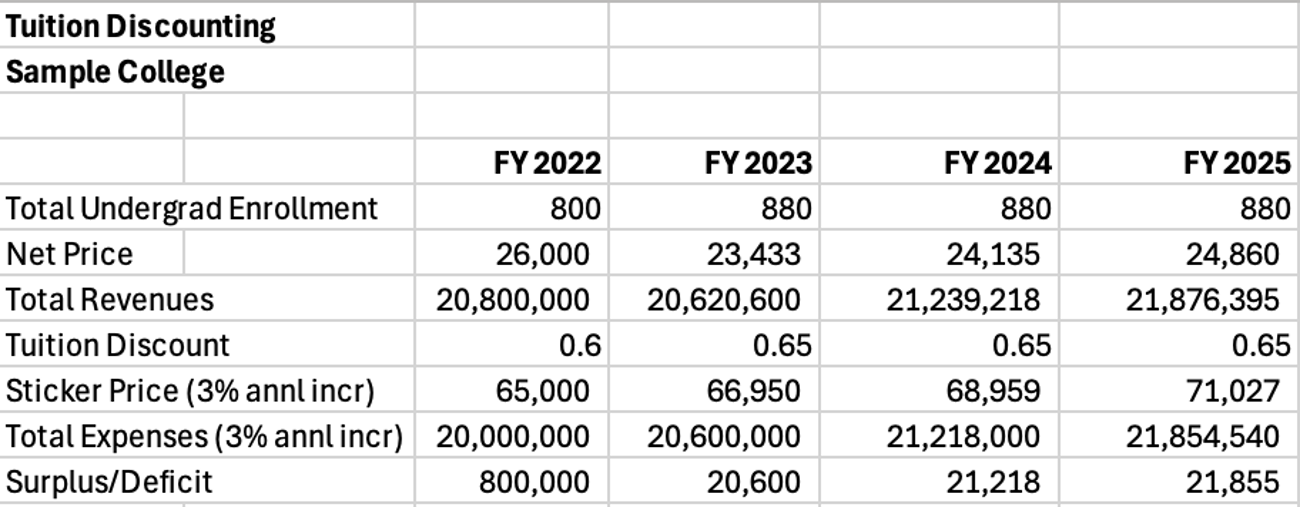

The only scenario that justifies increasing the discount rate used in the example is achieving a substantial increase in enrollments. In this case, I assumed a 10% growth (or 80 incremental students) in enrollments. Assuming the same increase in discount rate to 65%, the college is breaking even. See Table below.

As Dr. Lapovsky said in the Higher Ed Dive article, “We have too many schools. So they’re all fighting for students. I suspect my first table of the three previous tables is the more likely scenario.

With many small private colleges fighting for survival and enrollments, it’s hard not to think that offering more scholarship money than your closest competitor will make a difference in enrollments. As you can see from the first and second tables, the net price from every enrollment is critical to covering expenses at a small college.

Ben Unglesbee’s quote from Phillip Levine may be the one worth remembering: “It’s not good for anybody. It’s not good for the students. And it’s not good for the institutions…but there’s no way to get out of it.”

Hopefully, the colleges that find themselves above the NACUBO national average tuition discount rate can find a way to lower their discount rate and survive. With the upcoming demographic cliff and the increasing questioning about the ROI of college, the road ahead looks formidable.