From my earliest years in school, everything was about academic meritocracy.

America was in the middle of the Cold War with the Soviet Union and the “Space Race” to be the first nation to land a man on the moon. Schoolchildren were encouraged to be scientists and engineers to help America succeed.

In sixth grade, my parents heard about a Baltimore-area private school that recruited scholarship students through a competitive exam administered by the school. Those students who tested well were invited back for interviews with faculty, and those who navigated the interviews were offered a scholarship to attend the school.

I was a successful scholarship applicant invited to attend McDonogh School as an incoming seventh grader. Every student was prepared and strongly encouraged to attend college. McDonogh’s best students were encouraged to apply to elite schools regardless of their ability to pay. As a senior, I was ecstatic when I received a scholarship to attend Duke University.

There’s no need to continue describing my journeys through Duke and grad school at Tulane and the University of Pennsylvania. I received opportunities to attend and graduate from those institutions based on my academic successes and potential. The idea of a meritocracy based on intellect resonates with me thanks to its direct impact on my life.

How the Ivy League Broke America

Last week, The Atlantic published David Brooks’ latest article, “How the Ivy League Broke America: The meritocracy isn’t working. We need something new.” In his introduction, Mr. Brooks cites the decision by Harvard President James Conant to replace admissions criteria based on bloodlines with admissions criteria based on brainpower.

According to Mr. Brooks, Conant wanted to “create a nation with more social mobility and less class conflict. By reimagining college admissions criteria, Conant hoped to spark a social and cultural revolution.” The effect was transformative, according to Brooks. Status markers changed. More than 50% of upper middle class professionals graduated from elite schools.

Family life changed as a result of the “revolution.”. America wound up with two different styles of parenting. Working-class parents allowed their children to be kids, able to wander and explore. College-educated parents directed their children toward sequential activities related to skill-building and resume-building.

Schools changed. Recess time was reduced in favor of students spending more time taking standardized tests and Advanced Placement classes. Good test takers were funneled toward the meritocratic “pressure cooker.” Bad test takers learned that society does not value them the same way.

Brooks writes that over the past 50 years, America’s leadership class has grown smarter and more diverse. In addition, the percentage of well-educated Americans has increased, and bigotry has decreased. He cites a University of Chicago economic study that concludes that 40 percent of America’s increased prosperity from 1960-2010 can be explained by “better identification and allocation of talent.”

Nearly 60% of Americans believe our country is declining despite economic successes according to Brooks. More than two-thirds believe that “the political and economic elite don’t care about hardworking people.” He writes that trust in institutions has eroded to the point where, in the last three presidential elections, many voters have voiced their displeasure with elites by voting for Donald Trump.

The Six Deadly Sins of Meritocracy

Brooks claims that all of us are trapped in the system that Conant and his contemporaries at the Ivy League institutions implemented 70 years ago. He believes the six deadly sins of meritocracy are obvious. These are:

- The system overrates intelligence: “IQ became a measure not of what you do, but of who you are.”

- Success in school is not the same as success in life: “school is not like the rest of life.” In school, success is individual. In life, success is team-based.

- The game is rigged: Instead of sorting people by innate ability, it sorts people according to their parents’ wealth. Many elite schools admit more students from the top one percent of earners than from the bottom 60 percent.

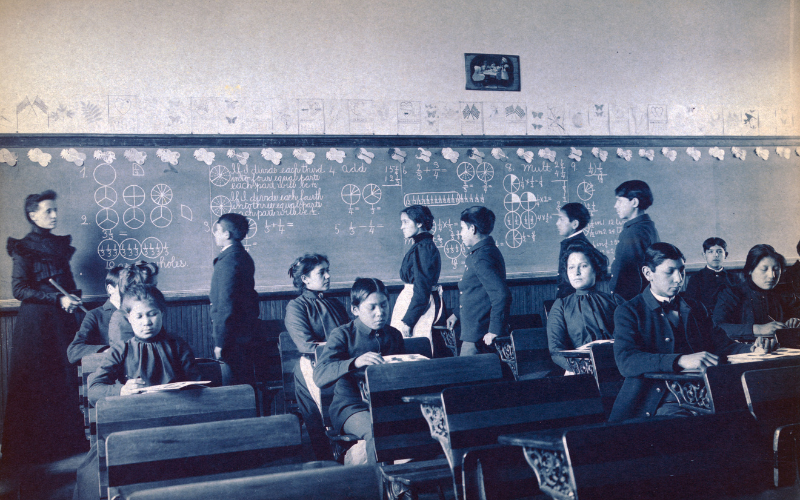

- The meritocracy has created an American caste system: The whole meritocracy is a system of segregation by education and contributes to segregation by race. For the past 50 years, the cognitive elite have withdrawn from engagement with the rest of society. Robert Putnam recognized this lack of community in his 2000 book, Bowling Alone.

- The meritocracy has damaged the psyches of the American elite. People raised in this sorting system tend to become risk-averse. At its core is the assumption that career success is the essence of life fulfillment.

- The meritocracy has provoked a populist backlash tearing society apart: Teachers behave differently toward students they consider smart. By adulthood, the highly educated and the less educated work in different professions, live in different neighborhoods, and have different cultural and social values. The most significant political divide is along educational lines.

How to Replace the Current Meritocracy

Brooks acknowledges that people have suggested in the past that we dismantle meritocracy. He states that human society throughout history has been hierarchical. “The challenge,” he writes, “is not to end the meritocracy; it’s to humanize and improve it.” A few recent events make changes in the system more important. These are:

- The Supreme Court’s ending of affirmative action means that colleges will have to find new ways to admit racially diverse classes and recruit students from underrepresented backgrounds.

- Thanks to the advent of generative AI, colleges should focus on finding and training the type of creative people needed to do what AI cannot.

- The recent campus Gaza protests and anti-Semitism on campus have caused a public relations crisis at elite universities. Now is the time to build a convincing case for these institutions’ value to America.

- The shortage in births is causing many schools to struggle with enrollment shortfalls. Colleges need to reinvent themselves to survive.

According to Brooks, step one is to redefine merit. The original system supported individuals’ cognitive skills. Brooks writes that non-cognitive skills are harder to quantify but are 2.4 times more important than math and reading scores in predicting a future student’s income.

Brooks proposes to redefine merit around four qualities that he deems crucial.

- Curiosity: Our current system doesn’t allow it to blossom. If you want to understand how curious someone is, it will show up in how they spend their spare time.

- A sense of drive and mission: people with these qualities go to where the problems are. They see their lives as a sacred mission.

- Social intelligence: find the people who are team builders, who have excellent communication and bonding skills.

- Agility: experts are generally not good at predicting future events. People with agility can switch mindsets and look at alternatives before choosing the best one.

Assuming you can redefine merit to include Brooks’ four qualities, what are the next steps for a rebuild?

Brooks suggests that we look at schools trying to make the entire school day look like extracurricular activities “where passion is aroused, and teamwork is essential.” Some of these schools are centered on project-based learning. Successful students must develop leadership skills, collaboration skills, and content knowledge.

To rebuild schools geared toward project-based learning, teachers and administrators must change how they measure student progress and ability. Some schools already provide students with more than just a report card. Electronic portfolios of papers, speeches, and projects help demonstrate students’ abilities.

More than 400 high schools have joined the Mastery Transcript Consortium, an organization that uses an alternative assessment mechanism. Brooks writes that no single assessment can predict a person’s potential. In a perfect world, teachers, guidance counselors, and coaches would collaborate and generate a five-page narrative about each student once a year. He suggests that a network of independent assessment centers could be built that use alternative tools to help students find the right college or training program for their core interests.

The current evaluation system in our meritocracy is built upon standardization. Everyone is placed on a scale with a normal Bell curve distribution. Brooks writes that we need an assessment system that prizes the individual over the system in a more complete way than a standard transcript.

We shouldn’t value only the superstars, but we should ask what each person is good at and how we can match them appropriately to the best job.

Opportunity Must Be Rebuilt

According to Brooks, to reach the highest peak in America, you must earn excellent grades in high school, score well on standardized tests, go to college, and, in many cases, graduate school. Avoiding dangerous pathways and bottlenecks along the way are problems you must avoid.

Brooks cites UCLA professor Joseph Fishkin who recommends that people be allowed to access a broader range of pathways to pursue. With more opportunities, gatekeepers have less power, and individuals have more power. Status and recognition are more broadly distributed.

America could deploy policy levers to expand opportunities, including reviving vocational education, making national service mandatory, creating social-capital programs, and developing a smarter industrial policy. He provides excellent arguments for each.

Finally, Brooks writes that we should create a meritocracy that selects for energy and initiative as much as for brainpower. Everyone should be able to “identify, nurture, and pursue the ruling passion of their soul.”

A Few Final Thoughts

I began this article by reflecting on my personal experience with meritocracy. Thanks to my academic achievements, I was given opportunities that many of my friends growing up did not have.

At the same time, the situation changed dramatically from when I attended high school and college (1970s) to today. Vocational schools were popular options for non-college-track students 50 years ago. Elite colleges were relatively affordable (I graduated from Duke with approximately $2,000 in student loans), and public universities were practically free for in-state students.

I’ve written about the pricing strategy for Ivy Plus universities and major public universities. None of them are very affordable for students in the lowest income quintiles, assuming that students from those quintiles are able to obtain an education that prepares them for the rigorous selection process.

I’ve also written about the increasing number of discussions about skills tracking. One of the best was a podcast about ranking colleges based on different career pathways with Michael Horn and Matt Siegelman. While the two stated that college was not for everyone, their ranking system was about colleges.

David Brooks is one of my favorite writers. I enjoy how he identified the problem (our meritocracy), provided some historical perspective, and incorporated multiple suggestions for changing the system.

The system must change. I don’t think it will change as orderly and logically as Mr. Brooks suggests. I think many non-elite private colleges are on the cusp of closing their doors if they don’t find ways to lower their prices and provide better student outcomes. The same applies to non-elite public universities.

Community colleges are affordable. Many of them have more students enrolled in non-credit training programs than students enrolled in credit-bearing courses. Their popularity is likely to increase if they focus on meeting the demands of students and employers, and provide a return on investment of the students’ time and money..

Public school choice and vouchers are becoming more popular. That trend is not going away even though it generally reduces the money available to public K-12 schools. That’s a wake-up call for states, counties, and even municipalities to make their public schools more accountable and relevant for everyone. Bring back vocational education. Not everyone should or needs to go to college.

AI will disrupt education, pre-Kindergarten through graduate school. The best schools are those that respond most quickly to the needs of their communities. Working together makes change less messy. Change will happen. It will not be neat. It will not be easy. It will not happen everywhere at the same time.

There will be winners. Like Mr. Brooks, let’s hope the pool of winners expands.