The Stanford Center on Longevity (SCL) is “an interdisciplinary research center that engages more than 100 faculty across Stanford’s seven schools. Last month, SCL issued a white paper titled “Building a Learning Society.” The paper is the product of a convening related to SCL’s initiative challenging outdated models of education, work, and retirement.

The five-page Executive Summary provides most readers with an excellent overview of the white paper’s contents. It’s a great sales pitch for anyone curious about what a “learning society” is and why the SCL is calling for the creation of one. In fact, it draws you into reading more.

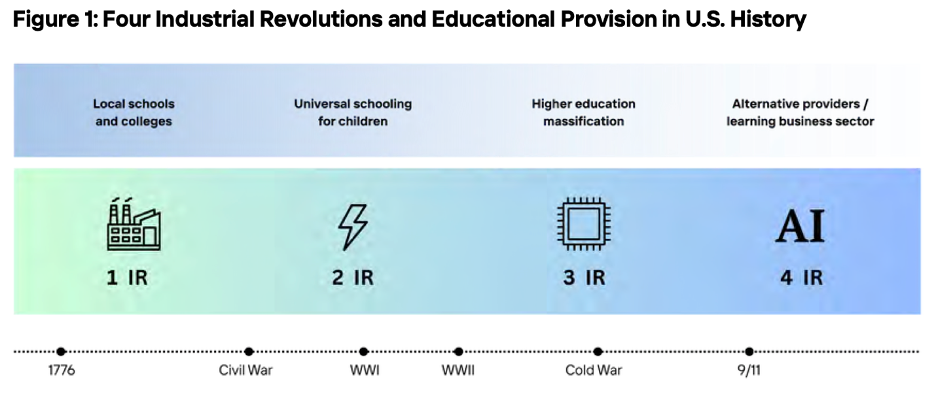

The authors point out that every notable period of change in America initiated by technology has been met by an investment in human talent. Whether it was the creation of schools during the first industrial revolution, the universal provision of public schools for all children during the second industrial revolution, or the massification of higher education after World War II, America stepped up to invest in its people.

The current and fourth wave of the industrial revolution, incorporating handheld supercomputers that connect us to knowledge and internet platforms, has not yet received the investment commitment of the first three. In fact, our commitment to schooling has become a limitation.

The “next great investment in people” will require moving away from structured school models to lifelong, flexible, and inclusive learning. This construction of the learning society is already underway. Still, America has not yet built a cohesive vision for the learning society’s foundation, nor has it aligned it with a thoughtful framework.

The average lifespan in the U.S. in 1920 was 55 years. Today, it approaches 80 years. For every citizen to benefit from an increased lifespan, our country must create pathways for mobility in education and employment. Employers will have to rethink how they “source, grow, and retain talent.” Educational institutions will need to continually adapt their offerings in response to the constant changes in work and everyday life. Governments will need to develop new ways to support talent across life and throughout adulthood.

Two Imperatives: Equip Americans for the Future of Work and Enable Opportunity

Changes in the implementation of technology, particularly AI, have already transferred human tasks to machines and are likely to continue to accelerate those transfers in the future as the technology improves. Changes in demographics and culture are additional incentives to invest in workforce talent over the 45-plus years of a worker’s career.

The authors of the white paper cite a recent Lightcast study that predicts a deficit of millions of workers in future years. That deficit will need to be filled by immigrants, offshoring, and the retention and retraining of workers.

Recently, modest gains in economic mobility have undermined the American Dream – where hard work is rewarded by rising prosperity over a worker’s lifetime. Per the authors, multiple factors such as unequal community circumstances for different class and racial groups, increasing costs of higher education, labor markets that discriminate against those without college degrees, and incarceration combine to sustain this problem. Furthermore, systemic practices in education and employment hinder opportunity. Educational credentials should enable opportunity, not serve as ceilings that block it.

The white paper’s authors describe the American Opportunity Index (AOI) as a joint venture that tracks the the careers of more than five million workers in the largest companies in the U.S. They write that AOI researchers have shown that companies differ on factors that implicate who has access to jobs, particularly those without college credentials. At the same time, their research suggests that companies play a significant role in shaping opportunities.

The authors use care work as an example. Care work involves “serving the health, well-being, and prosperity of others.” Care workers are underpaid, and the work is demanding in terms of time and attention. For opportunities to be enabled, the U.S. will have to change the organization and compensation of care work.

A Historical Perspective: The Schooled Society

The white paper’s authors provide a historical background of education in America through the lens of the four industrial revolutions. In Figure 1 below, they highlight the major education trends for each of the four revolutions.

The founding of the U.S. coincided with the timing of the first Industrial Revolution. The growth of cities and economic specialization was made possible through the early mechanization of agriculture and manufacturing. In America’s first 100 years, public investment in transportation and,communications, such as dams and canals, railroads, postal services, and the telegraph, stimulated the founding of local schools and colleges to provide people with education in numeracy, reading, writing, and mechanical knowledge to support their cities and businesses.

The second revolution began around the time of the American Civil War (1861-1865) and lasted until the end of World War I (1914-1918). During that period, manufacturing, transportation, and communications expanded thanks to technology. The flourishing U.S. economy attracted immigrants from Europe.

Concerns about America’s ability to govern itself with the mass immigration of new citizens led to a national commitment to formal education for all children, even though the education was distributed to the states and localities.

The authors write that universal literacy and numeracy enabled millions of people to contribute to a growing white-collar sector, as well as developed individuals who could build the machines, manufacturing processes, and financing mechanisms that underpinned capitalism. Even better was that this movement occurred with little regulation or investment from the U.S. government.

The massive organization of the U.S. defense manufacturing operation to support World War II and the Cold War spurred additional investments in education. The GI Bill was passed in 1944, the National Defense Education Act was passed in 1958, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act was passed in 1965, and the Higher Education Act was passed in 1965. These federal bills funded the expansion of college access from a “privileged few” to a national goal of millions.

Expanding college access led to the third industrial revolution in the last quarter of the 20th century. This included the development of nuclear energy, the expansion of the electronics industry, and the creation and expansion of programmable computing.

The fourth, and most recent, industrial revolution has occurred during the implementation and widespread adoption of the internet since the late 1990s/early 2000s as well as the open availability of mature Artificial Intelligence tools.

The researchers write that the nation’s colleges and universities and their many scientists and engineers were major contributors to these technological developments. The national investments in higher education have provided an economic return far more than the original contributions.

The higher percentage of college-educated citizens also contributed vitally to the nation’s cultural, artistic, and civic life. The societal benefits from America’s universal K-12 education and increased access to higher education are referred to as the School Society by social scientists.

Limits of the Schooled Society

In a schooled society, life “is organized into stages defined by people’s relationship to school.” Schooling, ranging from pre-K through 12th grade and then college for some, including undergraduate and graduate school (grades 13-20), creates expectations about where most learning occurs. Naturally, it’s at school; not at home, at play, or at work.

According to the researchers, the entire labor market and economic order of life have been defined in terms of “the rhythms and certifications of schools.” The researchers use 1965 as a benchmark for the beginning of an emphasis on federal funding on education rather than labor.

Fewer than 15% of adults between the ages of 25-29 had college degrees in 1965. Non-college educated white men held many well-compensated jobs in manufacturing. People starting out as workers were encouraged to pursue a single occupation that would last them their entire career.

Beginning in 1965 and continuing for years, federal and state governments established funding structures and regulatory agencies that emphasized public support toward education.

Education received the bulk of federal and state taxpayer financial support. The support was organized around the concepts of equality and student progress toward completing credentials. The education segment received the prestige associated with investing in the nation’s young people.

Labor, associated with services or manufacturing workers, received substantially less public funding and less academic attention. As a result, in less than 40 years, the national labor market was transformed by credentialism, specifically preferences created in hiring and promoting based on the attainment of college degrees.

Several economic factors accelerated the transformation of the labor market. First, the globalization of manufacturing caused the elimination of millions of manufacturing jobs in the U.S. Second, an emphasis on shareholder value over corporate stability led to the elimination of the social contract between employers and workers. Stable jobs were more frequently found in white-collar professions, specifically those held by college-educated workers.

The researchers note that “preferences for college credentials in hiring and promotion are legal forms of discrimination in the schooled society.” These preferences led to a massive increase in the number of high school graduates continuing on to college, and financial benefits to those schools that were able to accommodate the enrollment growth.

Academic credentials in the U.S. do not translate to legally recognized skills except in the highly regulated medical and legal professions, write the researchers. Employer preferences for college credentials led to economic prosperity for those with credentials, versus those without, even though few credentials define the potential or actual skills of their holders.

America never committed to funding education beyond K-12, and millions have paid for college with earnings, savings, and loans. As a result, U.S. citizens are burdened with $1.6 trillion in college loans, with no agreement on how to address the issue. Advances in technology have not led to a downward dip in the college costs trend either.

The good news, according to the researchers, is that economists agree that the fourth industrial revolution will reconfigure the conditions of work. Over the last decade, many entrepreneurs have leveraged technologies to create new platforms for learning. The World Economic Forum predicts that $10 trillion will be invested in the education sector globally over the next decade.

The Learning Society

Society in the future will distinguish between learning and schooling, according to researchers. Schooling occurs in designated places, whereas learning takes place everywhere. Once society recognizes that learning occurs throughout life, a different human capital enterprise will emerge.

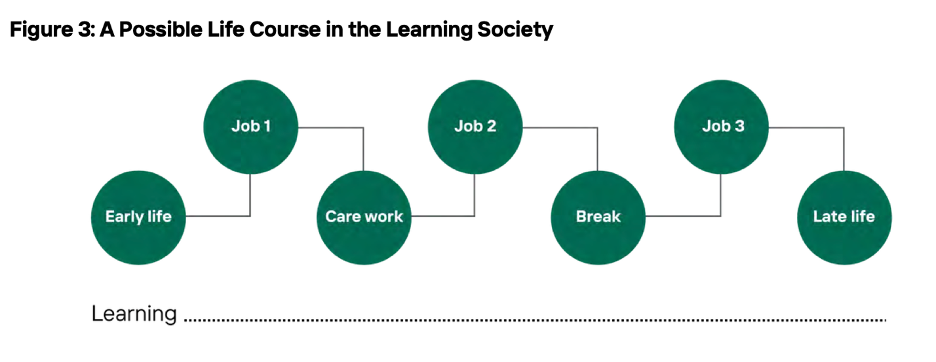

A possible pattern for learning and working is illustrated by the researchers in Figure 3 below.

In a learning society, people will be freed from the notion that all learning takes place in schools. The authors write that people and their employers will be able to take advantage of a myriad of learning sources available in an expanded learning marketplace. Many of these sources will be embedded into the cadence of the workplace. Others will be available in the form of games and VR. Legacy schools will remain, but will reorganize into hubs for the aggregation and delivery of learning and other human opportunities from many different providers.

A four-year degree has become a “talent bottleneck,” write the authors. A rapidly growing education technology sector is providing the tools and platforms for alternatives to learning. However, the learning society won’t come to fruition on its own because of several obstacles, the most notable of which are:

- The non-cumulative, a-scientific character of innovation in the ed tech sector,

- The data anarchy for any learning opportunities outside of legacy schools,

- The disincentives for employers to invest in workforce talent development, and

- The profoundly unequal contexts in which children begin their learning.

To overcome these obstacles, the researchers recommend design principles for the framework and implementation of a learning society.

Nine Design Principles

The lack of a shared vocabulary, metrics, and goals for coordinating investments nationwide triggered the recommendation of the following nine design principles.

-

Schools are essential for learning and civic life.

While the locations where learning occurs will continue to expand, the researchers write that schools will remain one of the few institutions with a mandate to reach all children. At the same time, schools must prepare young learners for a future of life, work, and learning that has not been developed.

The authors mention the School Superintendents’ Association Public Education Promise: Future Ready Framework, which emphasizes expanded “basics” to include digital fluency, financial competence, AI literacy, and social-emotional capacities that support adaptability, well-being, and civic engagement.

Educators’ roles will continue to be vital but will evolve. Their value proposition will be in their ability to help students “navigate ambiguity, pose meaningful questions, and exercise sound judgement.” All of these are components of critical thinking and tenets of a liberal arts education.

The extension of Americans’ lifespan, as well as the presumed extension of their work lives, will mean that many will return to school. Their roles will range from mentor to learner. Future schools will bridge generations by preparing children for lifelong learning, retraining adults, and providing spaces where both adults and children can learn from one another.

-

Credentials are means, not ends.

The researchers note that America’s Schooled Society revolved around getting people two primary credentials: high school diplomas and college degrees. Their value could be “measured by observing statistical associations between credential attainment and specific outcomes such as occupational mobility, lifetime earnings, and physical health.”

When the credentials became ends in themselves, little progress was made on actual learning, employment progression, and people’s abilities to make informed decisions about their lives.

The researchers argue that a national conversation is needed to determine the objectives and goals. They suggest that three worthy goals might be agency, mobility, and resilience.

Agency is defined as the ability for people to imagine possible futures, understand how to pursue those futures, and have the tools to get there.

Mobility is defined as the ability of people to change the work they do by either moving up an occupational ladder or by moving from one domain to another.

Resilience is defined as the ability of individuals to anticipate, cope with, and profitably adapt to change.

-

Design for change across longer lives.

Investments in humans are cumulative. Investments made later in life build on those made in early life. The evidence is substantial to support the benefits of early-life education toward later-life accomplishments such as earnings, lifespan, and physical health. The researchers write that this has led to debates as to when to make later investments in people.

A substantial percentage of America’s public investment in learning has been in K-12 schooling. The earliest years (PS, PK) are underfunded despite evidence of the learning capabilities of children under five. The later years (post-secondary) are underfunded as well, primarily because of the substantial cost of K-12 education.

Developers and architects of a learning society should have the freedom to opt for a more balanced investment strategy than what our governments provided in the twentieth century. A new strategy would acknowledge the importance of learning in the first two decades of life, but, the researchers write, it would not stop there.

Architects of a learning society would recognize that rapidly changing technology would reward an investment strategy that enables people to continually learn and adapt to different kinds of work over the extended years of their lives.

-

Build infrastructure for caring.

The segregation of a local school from work and home as the official site for learning created many negative outcomes. It forced adults to simultaneously care for children and their elderly relatives, earn post-secondary credentials, and work. It forced people to work double and triple shifts to include one for the job, one for care, and one for themselves. This impacted their physical and mental well-being, as well as their job satisfaction.

An excellent opportunity for the learning society will be the “reconfiguration of institutional infrastructure so that care work, paid employment, and learning are truly simultaneous and complementary.”

-

Working is learning.

The authors write that a learning society recognizes that the best learning occurs through hands-on experience. Even more learning occurs when people work in teams or alongside more experienced colleagues. They add that employers, entrepreneurs, and educators are already at work developing contemporary forms and business models that commingle work and learning.

In addition to developing these modes of learning, the researchers write that an applied science should be designed to identify, instrument, and measure returns on these new modes as well as to encourage and reward them.

The authors emphasize a need to encourage employers to embrace their role as sites and agents of learning. Employers and others will also need to develop new mechanisms for signaling skills and capabilities as workers advance, whether or not they hold traditional credentials.

Rethinking work as learning will be particularly difficult for schools and colleges. The authors write that the blurring of lines between learning spaces and workspaces has always been fruitful for experts in either domain. Programs in business, health, engineering, and education have flourished with these blurred lines for years as they’ve brought in outside experts to teach and share their experiences with learners.

-

Build an economics of learning.

It’s very rare that researchers identify, measure, or model learning that occurs outside of schools. They also rarely measure the economic returns of that learning. This means that workplaces and households are not credited for the growth in human capital that occurs through them.

In today’s digital world, it is possible to observe and document learning simultaneously with a learning treatment applied to a learner or worker. This provides opportunities to “provide, improve, measure, and reward learning opportunities in every domain of human activity.”

The builders of a learning society will need to develop “a social science that: (a) recognizes that learning happens in every social sector, (b) instruments learning in these sectors for measurement, and (c) models costs and returns to learning for individuals, organizations, and society.”

Being able to measure and compare returns to new modes of learning investments will encourage additional learning investments.

-

Think carefully about skills.

The researchers write that they are “struck by our thin working conception of skills.” They advise architects of the learning society to be careful about their definitions of skills. To do this appropriately, they suggest that the architects carefully parse definitions of capacities, skills, and craft.

Capacities are defined by the authors as “generalized abilities that enable learning and adaptation in the face of uncertainty.” Once obtained, the recipient benefits from them over a lifetime. They include:

- High-level literacy and numeracy,

- Critical thinking,

- Inquisitiveness,

- Persistence,

- Patience,

- Empathy for other points of view, and

- Ability to negotiate and work collaboratively.

Skills are defined by the authors as narrower and (frequently) context-specific abilities. They are essential for livelihood and productivity, but their “half-lives” are often short.

Craft is defined as the “commingling of capacity and skill in particular domains of endeavor.” It implies a “‘feel for the work’ that comes with steady practice.” Craft gives a worker or team its signature and is frequently a point of pride.

Recognizing these three different components of capabilities will enable the learning society’s architects to avoid leveling human activity to skills alone.

-

Design for transitions

Life is full of transitions, and they are frequently expensive and impactful on the human psyche. Learning opportunities are often used for smoothing transitions. Attending or returning to college has been a frequent choice by adults to smooth the transition to a career change.

Employers who develop practices that recognize, celebrate, and reward transitions will enhance the experiences of their workers. Public policies that support people who move between jobs, geography, and life stages will lead to the creation of a more dynamic workforce.

-

Make the learning society a joint venture.

Previous industrial revolutions involved all participants working across sectors. Coalitions of employers, religious leaders, civic leaders, researchers, and philanthropists helped build the schooled society in addition to local, state, and federal governments. Development of the learning society must be collaborative across sectors as well.

We cannot presume that the funding and governance structures of the schooling society will be the same as the funding and governance structures of the learning society. The researchers cite roadblocks developed by the schooling society that include:

- Complex school bureaucracies and procurement criteria,

- Inflexible postsecondary accreditation bodies,

- Public funding tied directly and exclusively to programs bearing college credit,

- Public postsecondary and workforce agencies that work independently of each other, and

- Reciprocal suspicion between legacy academic institutions and new providers.

Policymakers planning for a learning society must include many parties beyond schools, colleges, workforce agencies, and regulators. Too much capacity and intelligence exist in technology, venture capital, and human resources and training offices of businesses to ignore.

The researchers point out that there are at least three broad areas for cooperation among the learning society architects and leaders. These are: data systems, finance, and governance.

Public data systems are currently fragmented across state and federal agencies that serve sectors such as education, employment, and health. Reliable and transparent public data are critical for integrating and benchmarking information across all sectors and domains. At the same time, employers maintain their own datasets that are seldom integrated into the public sector data. No federal government standards currently exist for integrating or making this data interoperable.

Local, state, and federal governments have generally funded K-12 education under the premise that all citizens are entitled to a high school diploma. That same entitlement has not been applied to higher education. It was also not applied to any of the funding mechanisms for higher education. With people being required to learn more over a longer period, the authors write that we must develop new mechanisms to pay for talent development without debt.

Building systems that will enable us to plan, observe, and improve returns on investment in learning will require some type of governance. The researchers advocate for developing mechanisms for pooling resources, setting standards, and coordinating decision-making among many public and private entities. This is not a new idea; it’s already in place in scientific communities and in sectors like air and maritime navigation. An organization designed to govern the major providers and influencers in the learning society will be large and heterogeneous. It will also have a sustainable business model and shared purpose.

A Bold and Audacious Vision

The white paper’s authors write that “we live in a world in which responsibility for lifelong employment and economic prosperity falls on individuals, yet far too many of us do not have adequate resources to invest in our own futures.” It is natural that the current environment of AI-enabled technologies feels less like progress to many and more like another impediment to achieving the American Dream.

The authors call for a bold and audacious move. Build a learning society that will bring the American Dream into more households. They write that “new technologies can be used to deliver learning opportunities at greater speed, at lower cost, and with personalized precision.”

America has the talents and resources to build a learning society. America lacks a “shared vision for what the future should look like and a web of relationships between schools, higher education, and business that will enable the collaborations necessary for cumulative change at scale.”

Seeding relationships and collaborations, developing shared language, and establishing metrics for measuring progress, as well as fostering reciprocal trust, are the next steps in the quest for a learning society that will enable prosperity for its citizenry.

A Few Additional Thoughts

As the white paper indicates, there were three in-person convenings of the cohort of Futures Fellows and an unspecified number of virtual meetings over a 12-month period. The authors do not claim that their work is a consensus document and note that the Fellows do not agree on every point presented. However, they present it as a collaborative document designed to provoke big-picture thinking and discussion.

As mentioned throughout the paper, many initiatives are already underway that could provide a few of the underpinnings of the foundation of a learning society. Do I believe that it will develop along the nine design principles recommended by the paper’s authors? No. Do I believe that one of the outcomes of a learning society supplanting the schooling society that we relied on for our last industrial revolution will be the increased dispersion of wealth across our citizenry? Sadly, I have major concerns that such an outcome will occur.

One of the outcomes of our internet-connected era is an increased divide among partisan groups. Building the collaboration necessary to incorporate the suggested design principles, as well as data, finance, and governance, will be painful and may never occur on a national level.

I applaud Stanford’s Center on Longevity for assembling such a noted group of experts to discuss a major issue like the transition of the schooling society to the learning society. Long term thinking is not something that originates very often in the halls of Congress or in agencies that comprise our Executive Branch.

I think the white paper will be an excellent piece to stimulate discussions at the federal level. At the same time, I give the document’s recommendations a better chance of being implemented in a state whose political leaders recognize the value in building a learning society for its citizenry and its economy.